Rows: 17,414

Columns: 10

$ timestamp <dttm> 2015-01-04 00:00:00, 2015-01-04 01:00:00, 2015-01-04 02:…

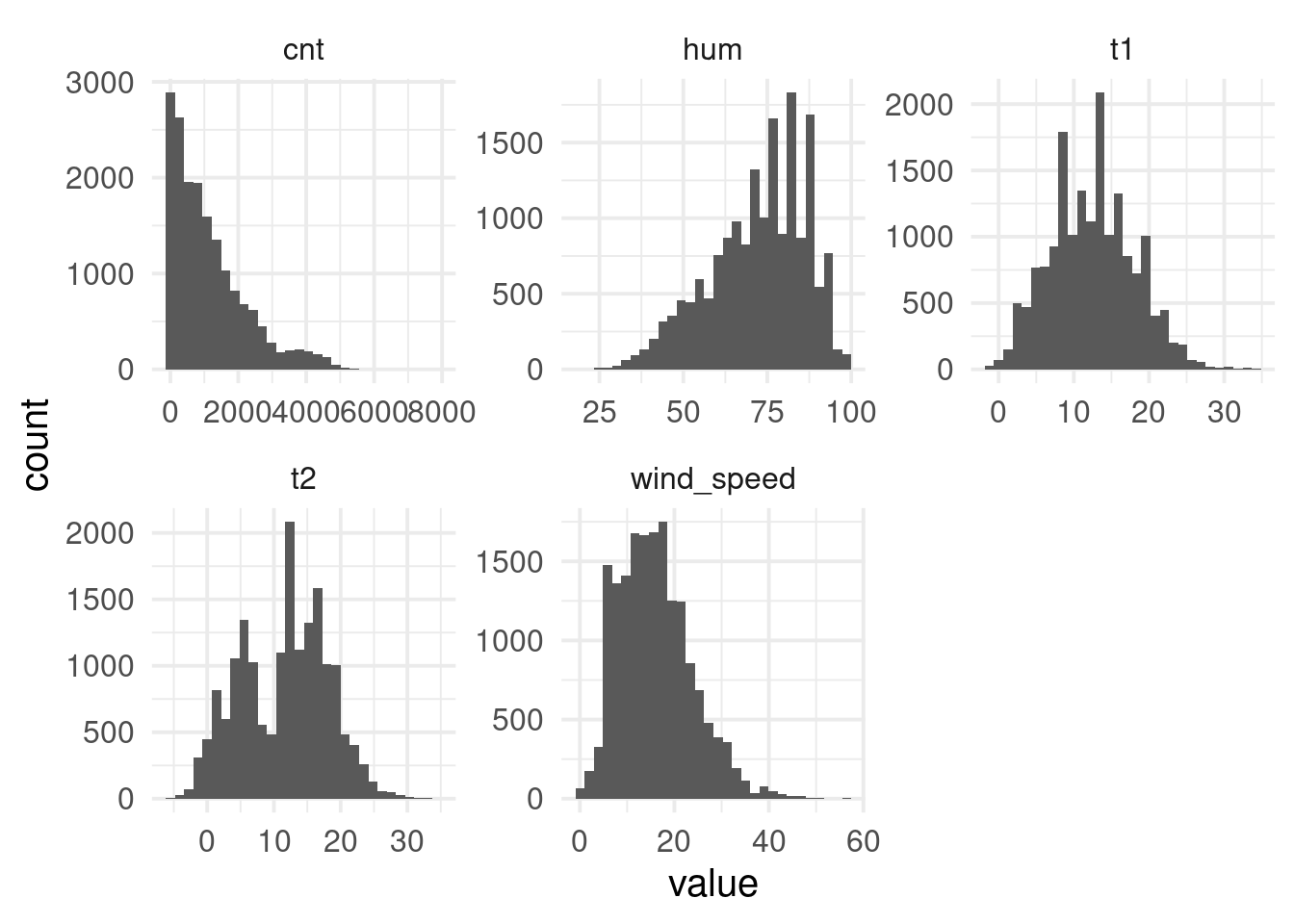

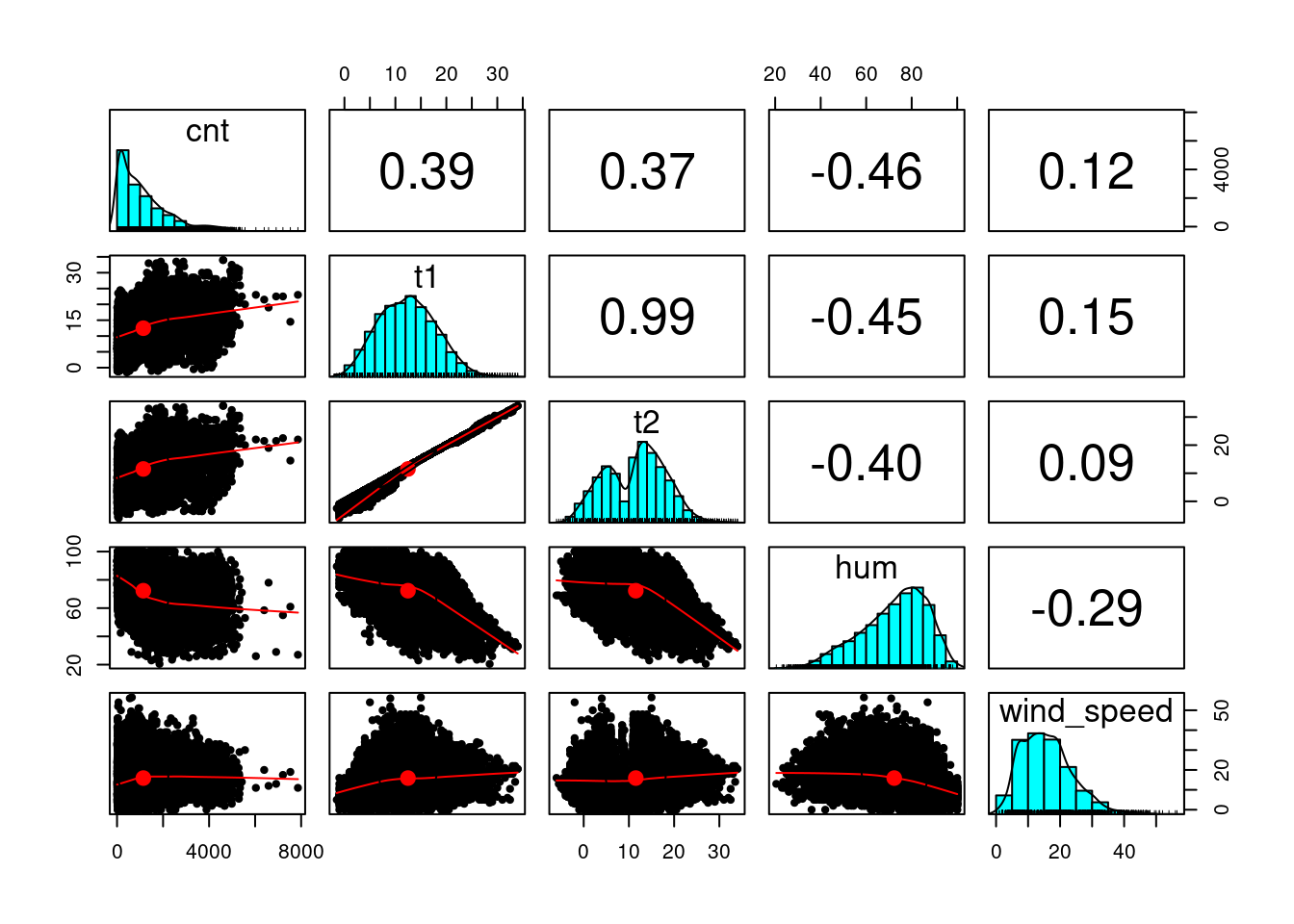

$ cnt <dbl> 182, 138, 134, 72, 47, 46, 51, 75, 131, 301, 528, 727, 86…

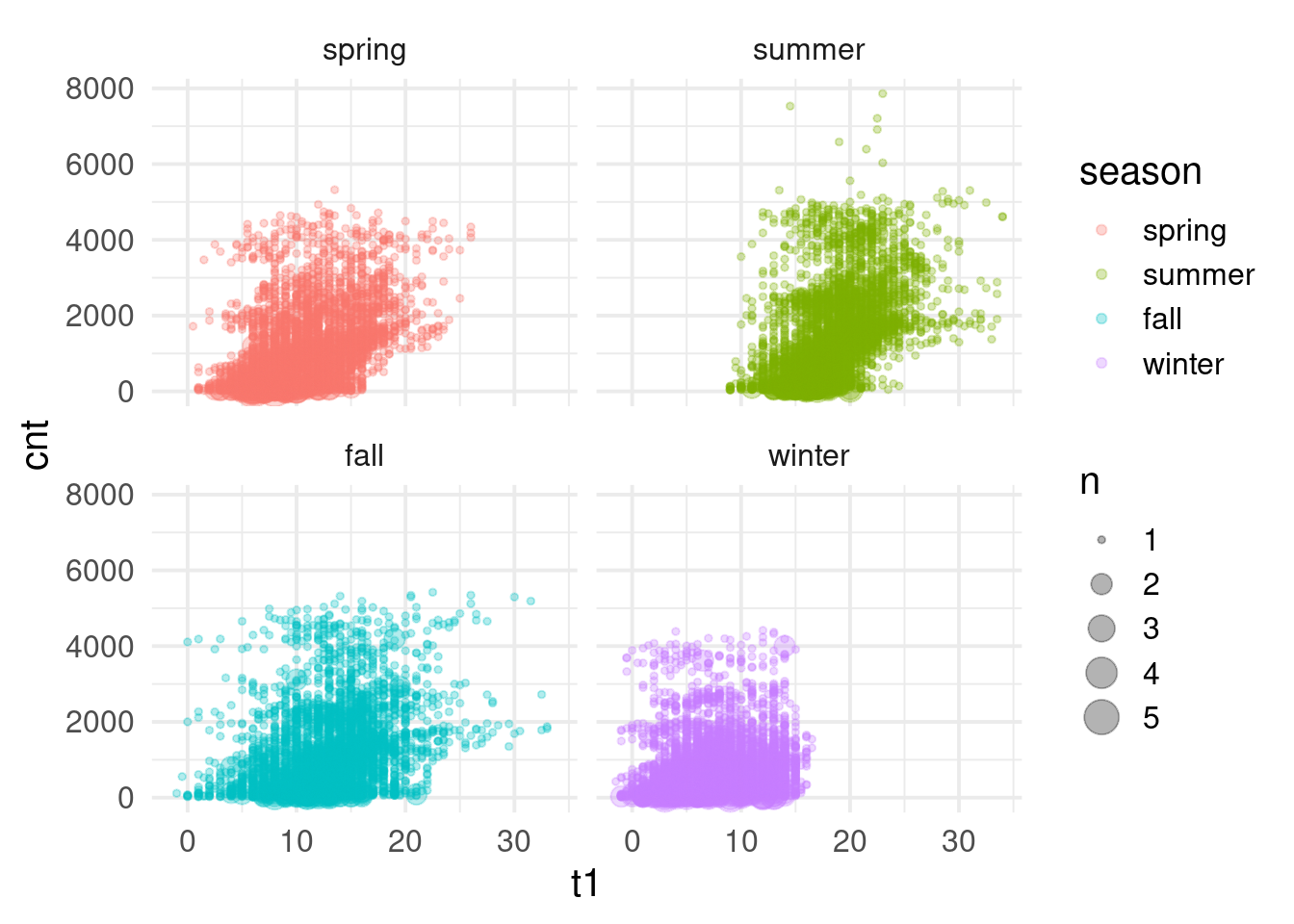

$ t1 <dbl> 3.0, 3.0, 2.5, 2.0, 2.0, 2.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 2.…

$ t2 <dbl> 2.0, 2.5, 2.5, 2.0, 0.0, 2.0, -1.0, -1.0, -1.0, -0.5, -0.…

$ hum <dbl> 93.0, 93.0, 96.5, 100.0, 93.0, 93.0, 100.0, 100.0, 96.5, …

$ wind_speed <dbl> 6.0, 5.0, 0.0, 0.0, 6.5, 4.0, 7.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 12.0, 1…

$ weather_code <dbl> 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 4, 4, 4, 3, 3, 3, 4, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, …

$ is_holiday <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

$ is_weekend <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, …

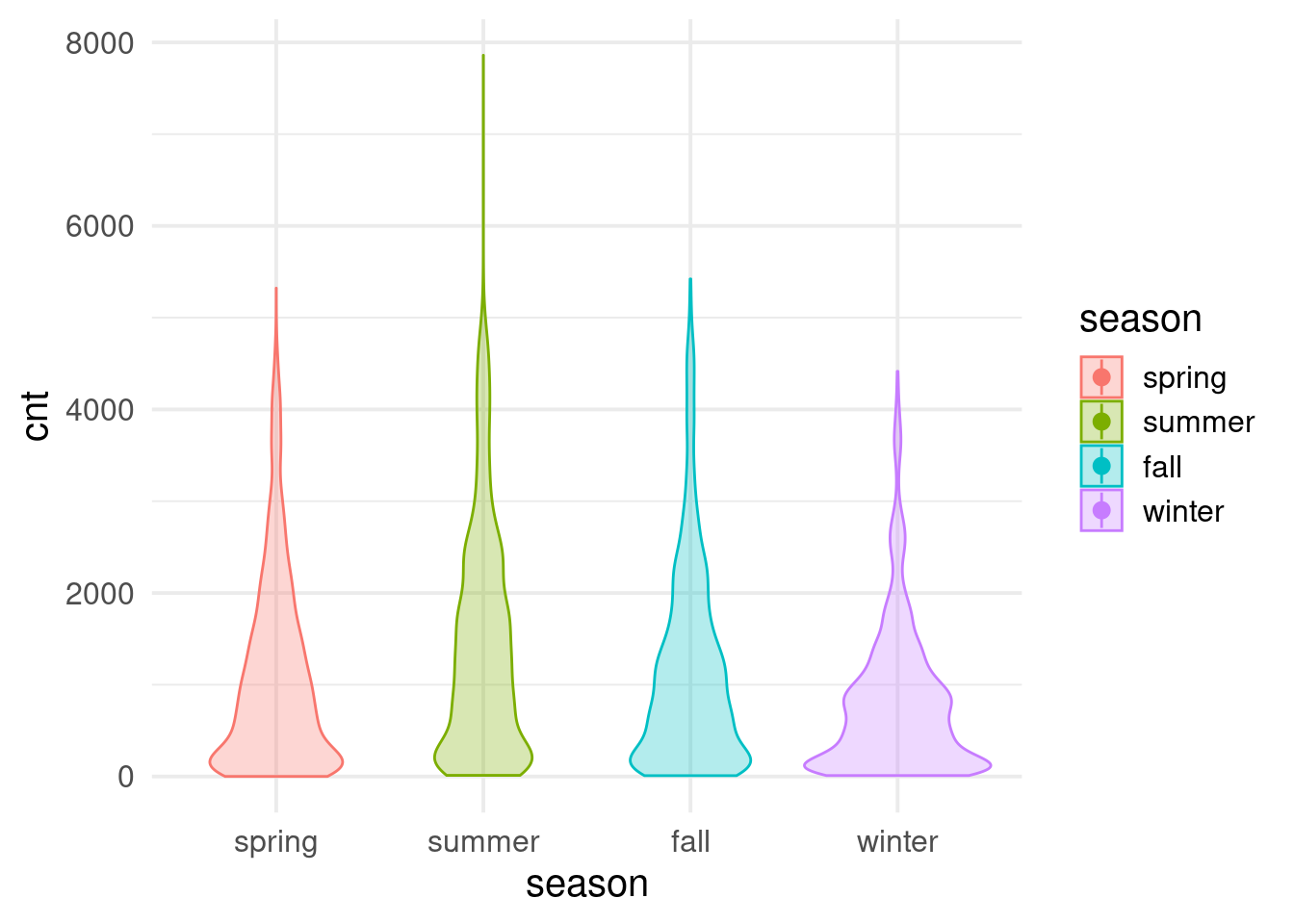

$ season <dbl> 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, …