Rows: 437

Columns: 28

$ PID <int> 561, 562, 563, 564, 565, 566, 567, 568, 569, 570,…

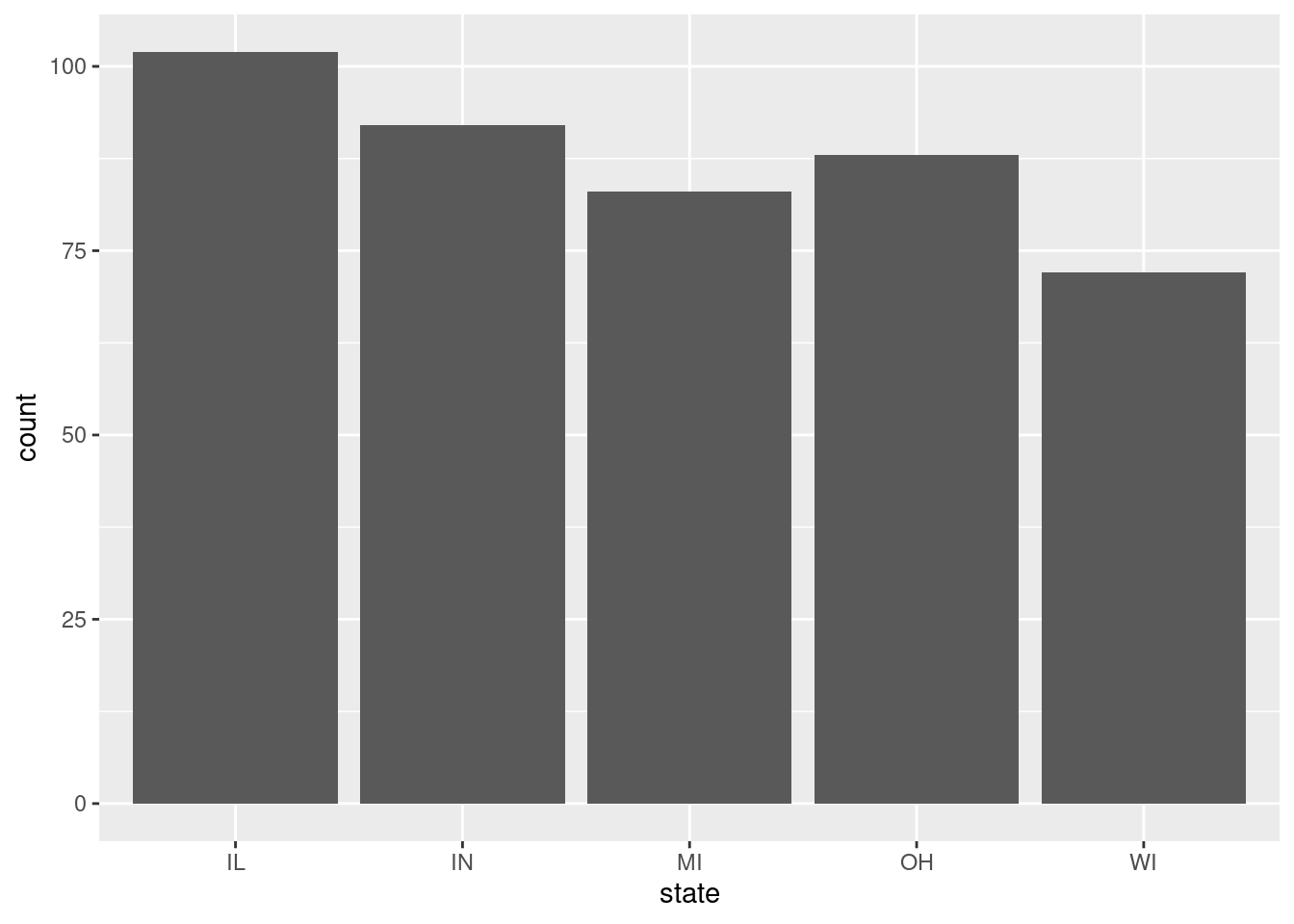

$ county <chr> "ADAMS", "ALEXANDER", "BOND", "BOONE", "BROWN", "…

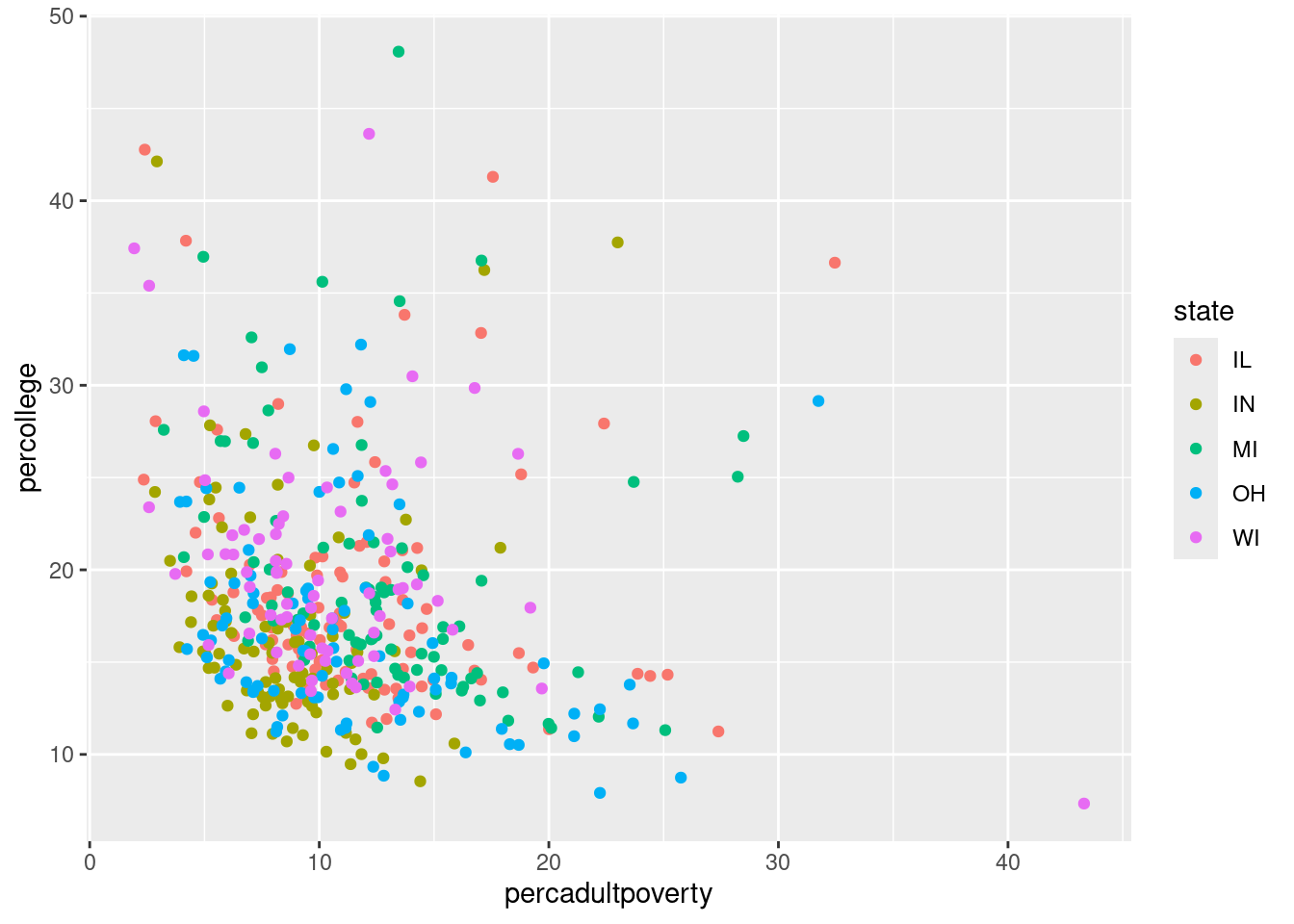

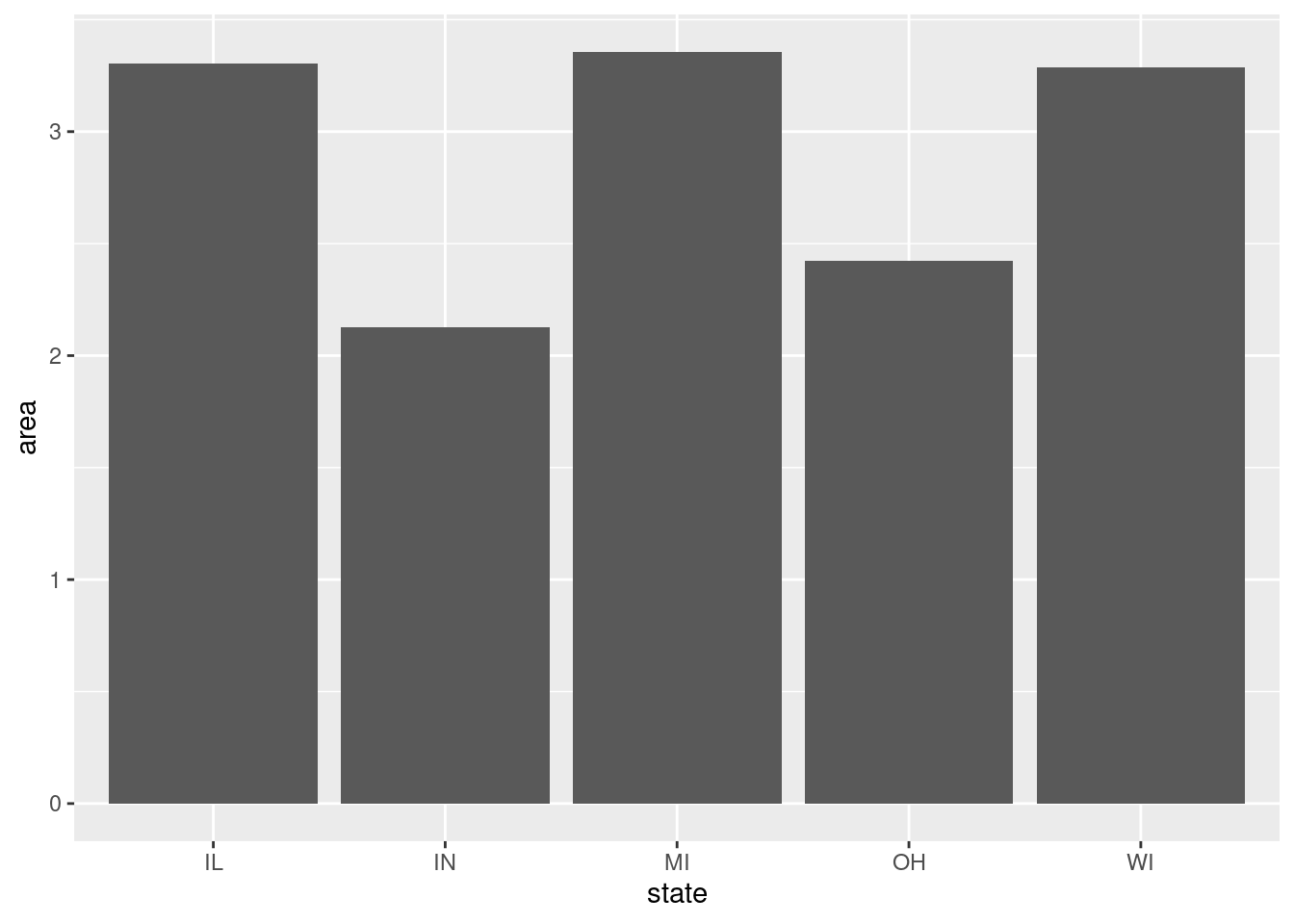

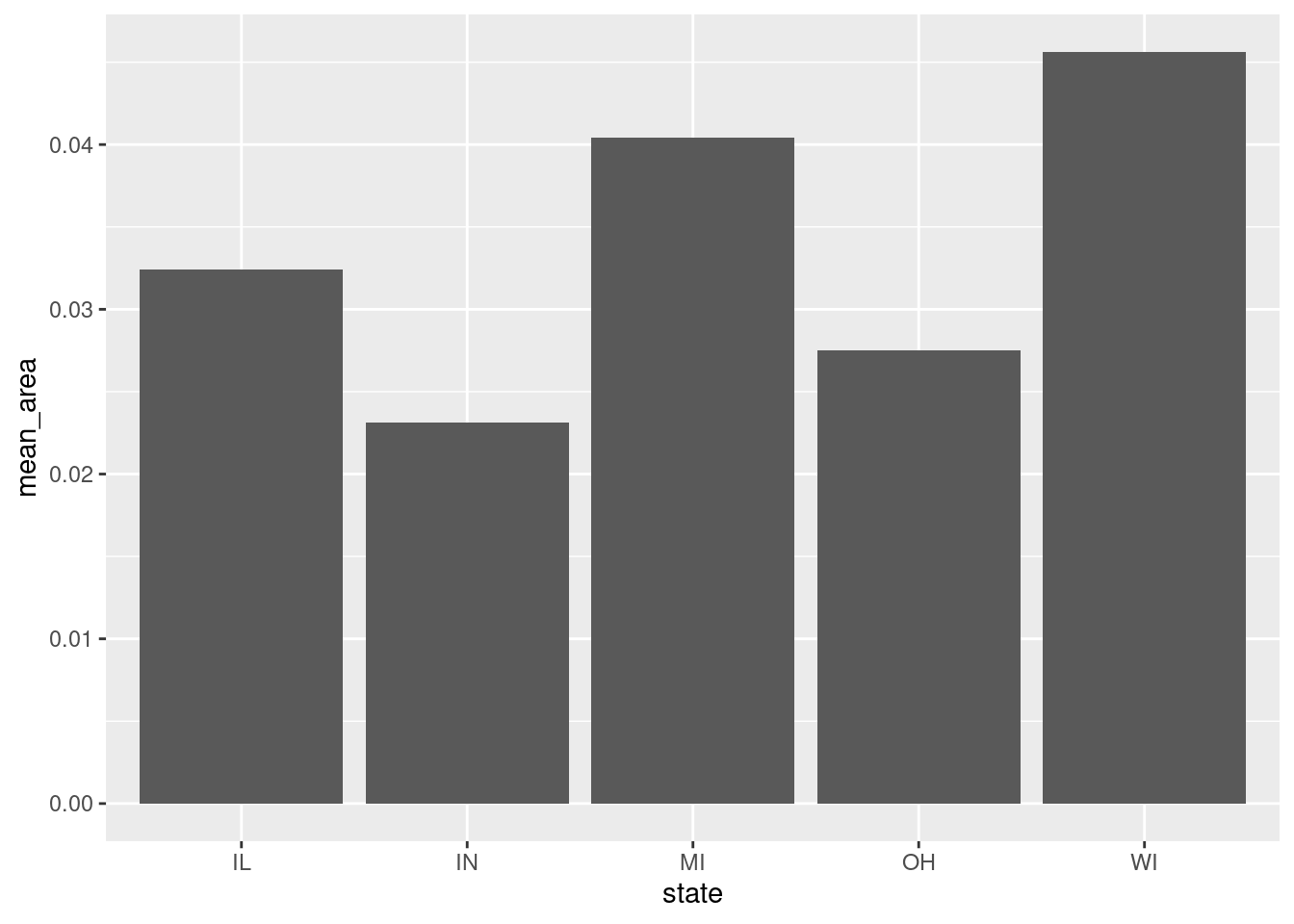

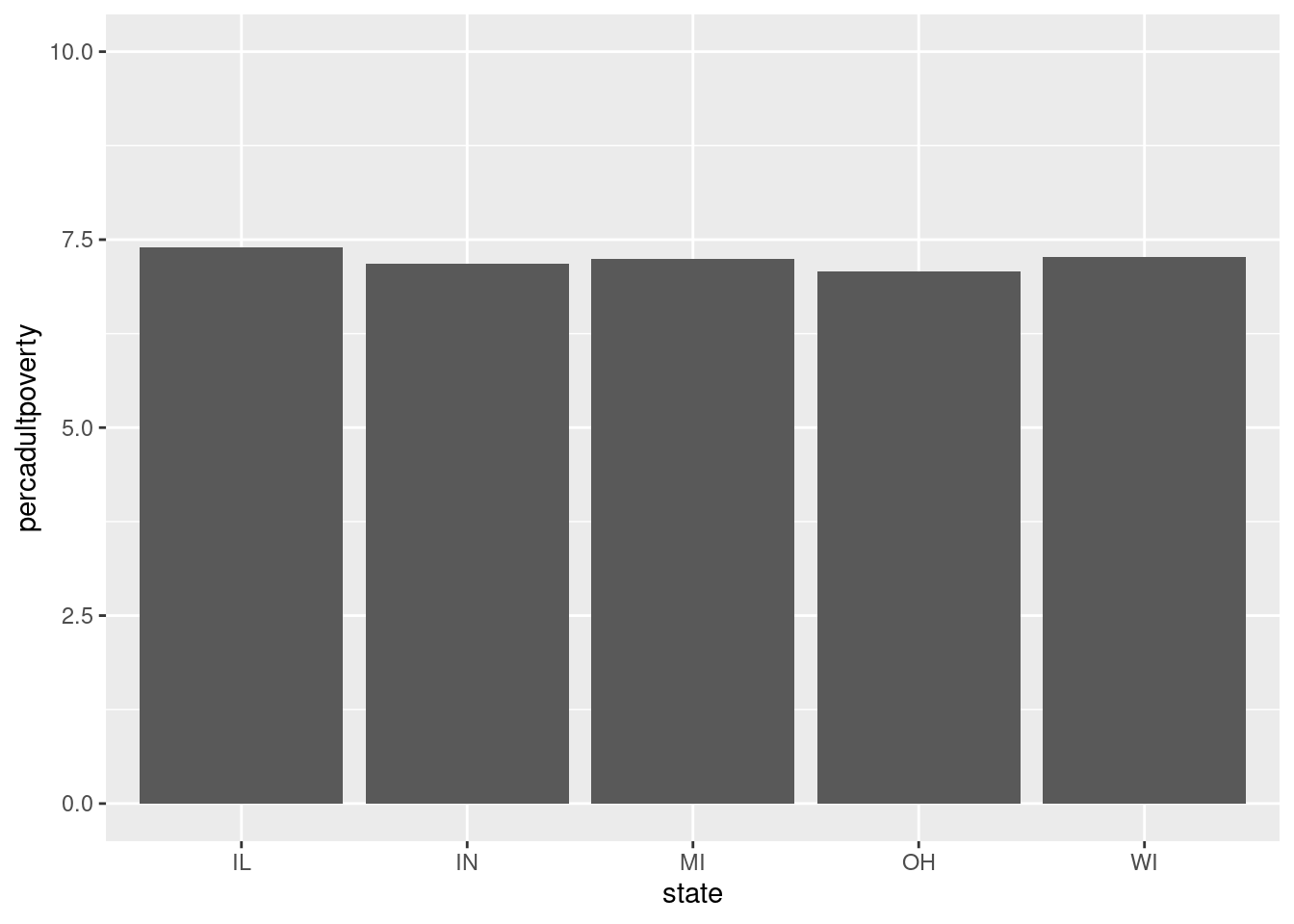

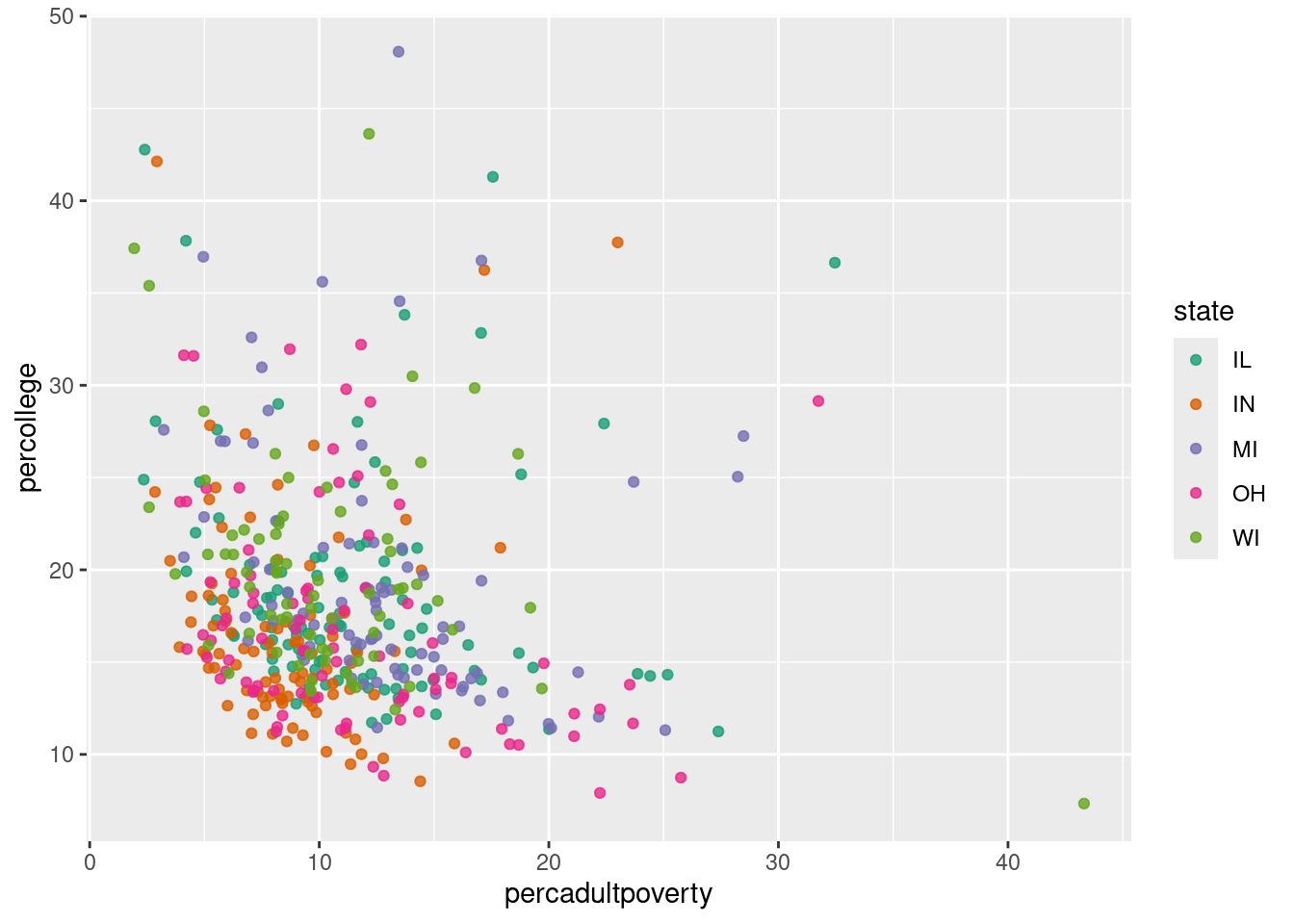

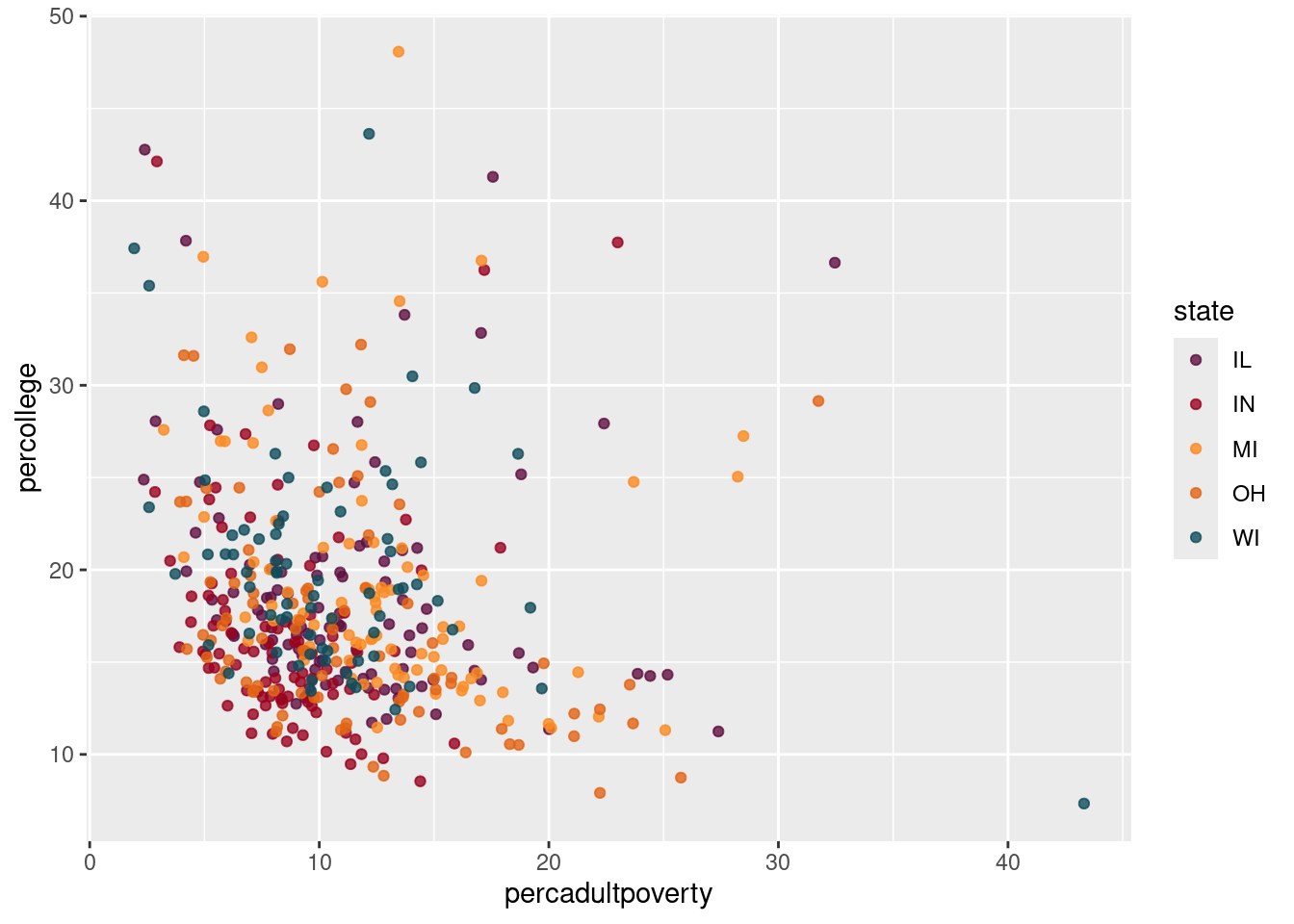

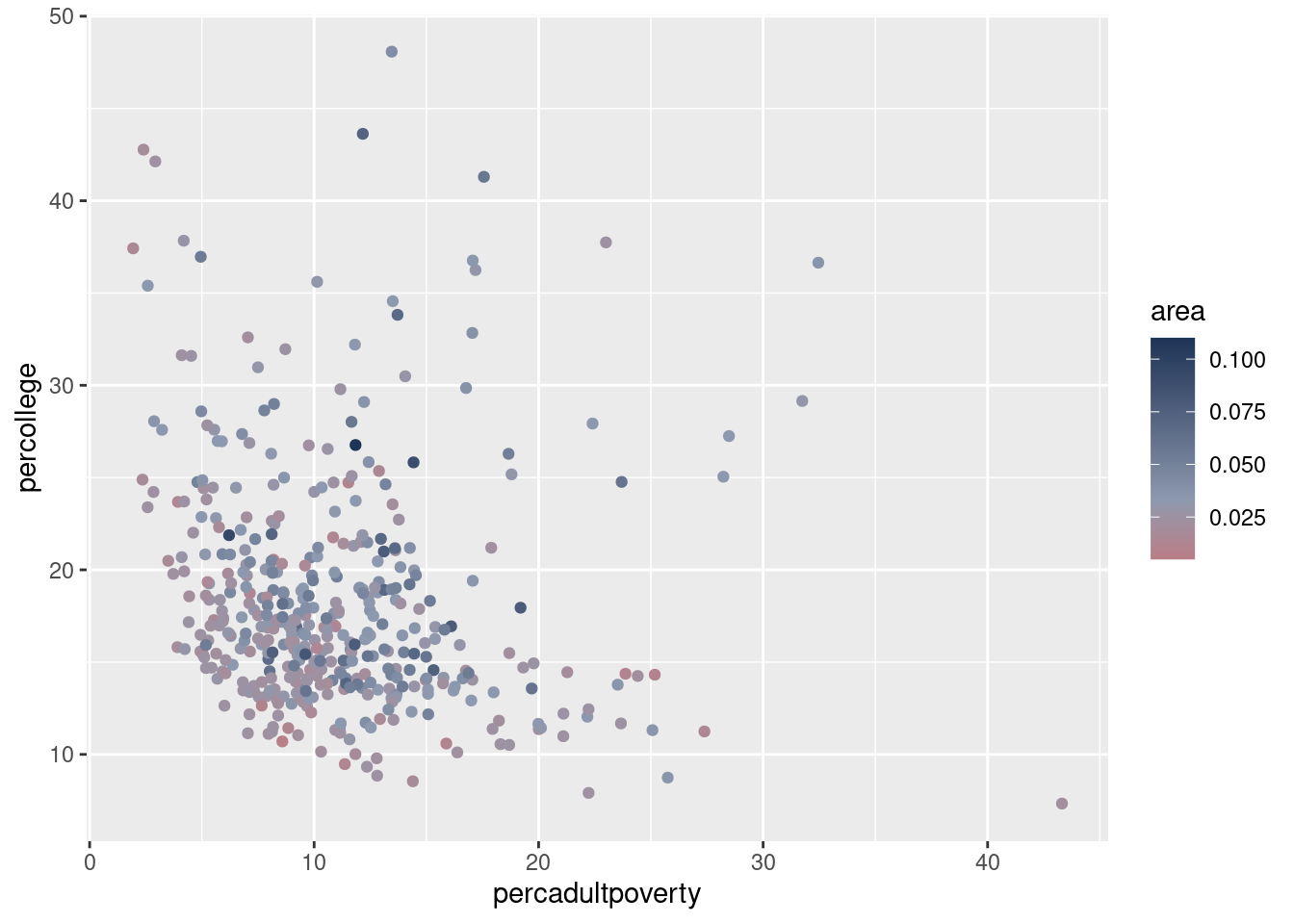

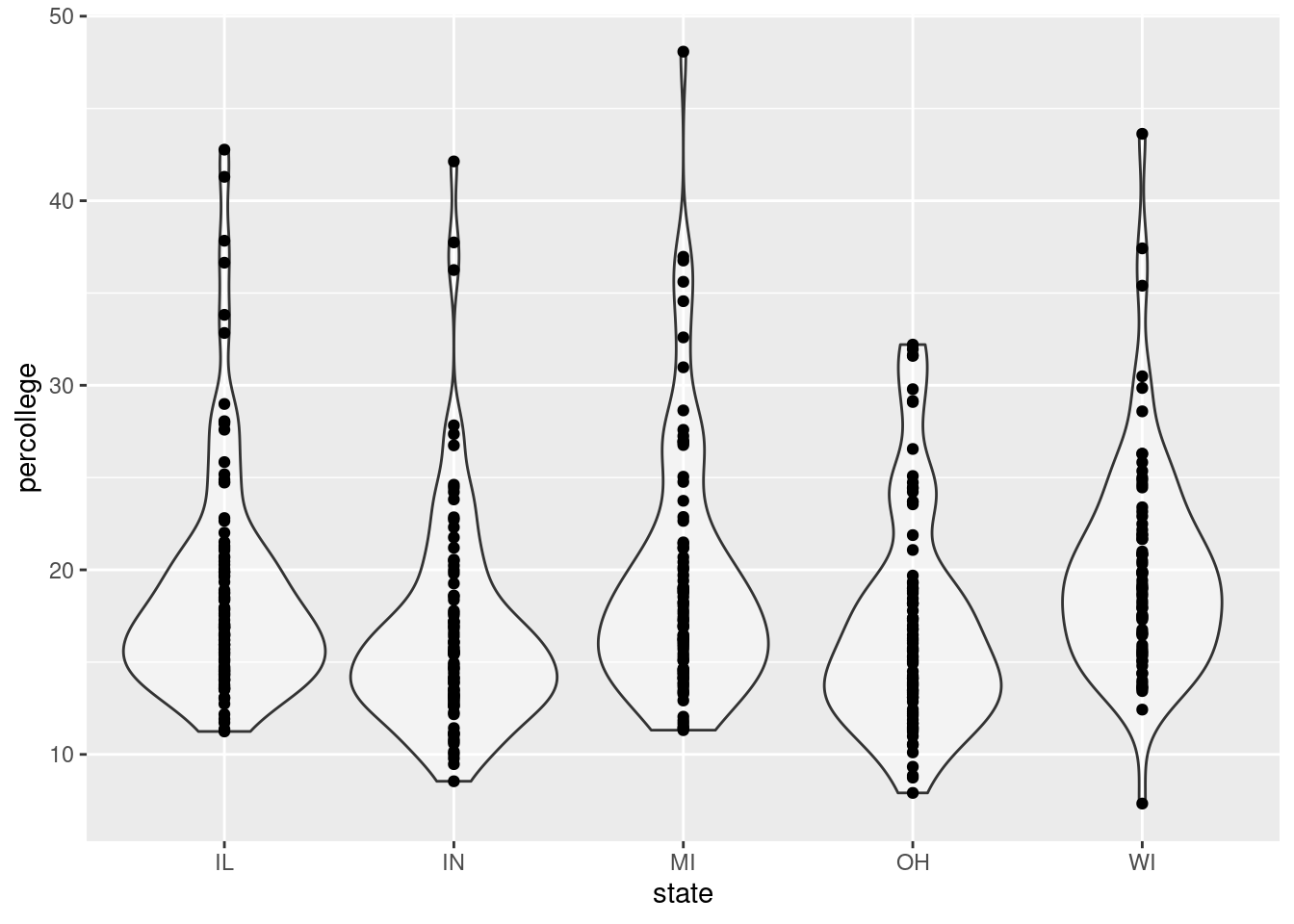

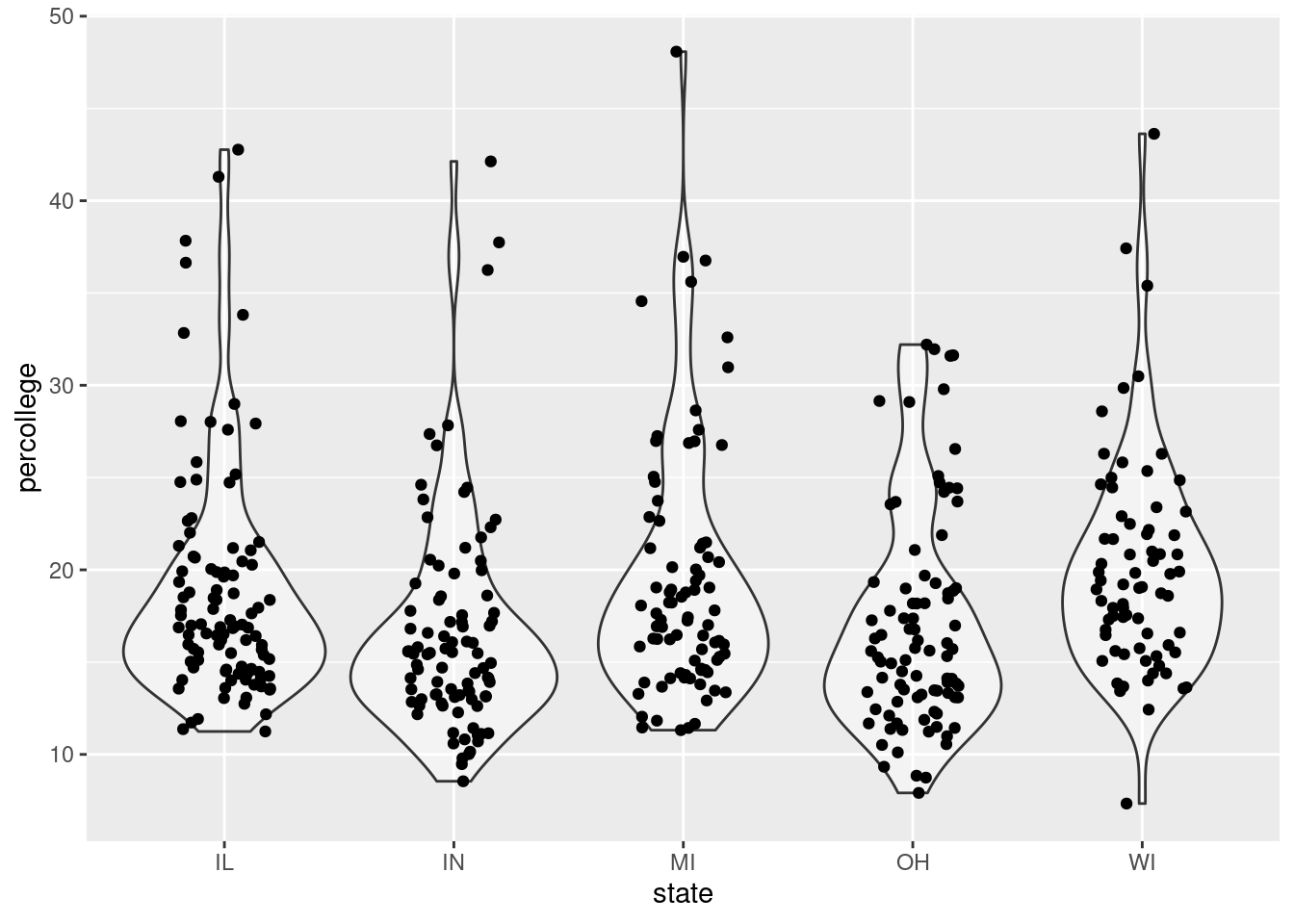

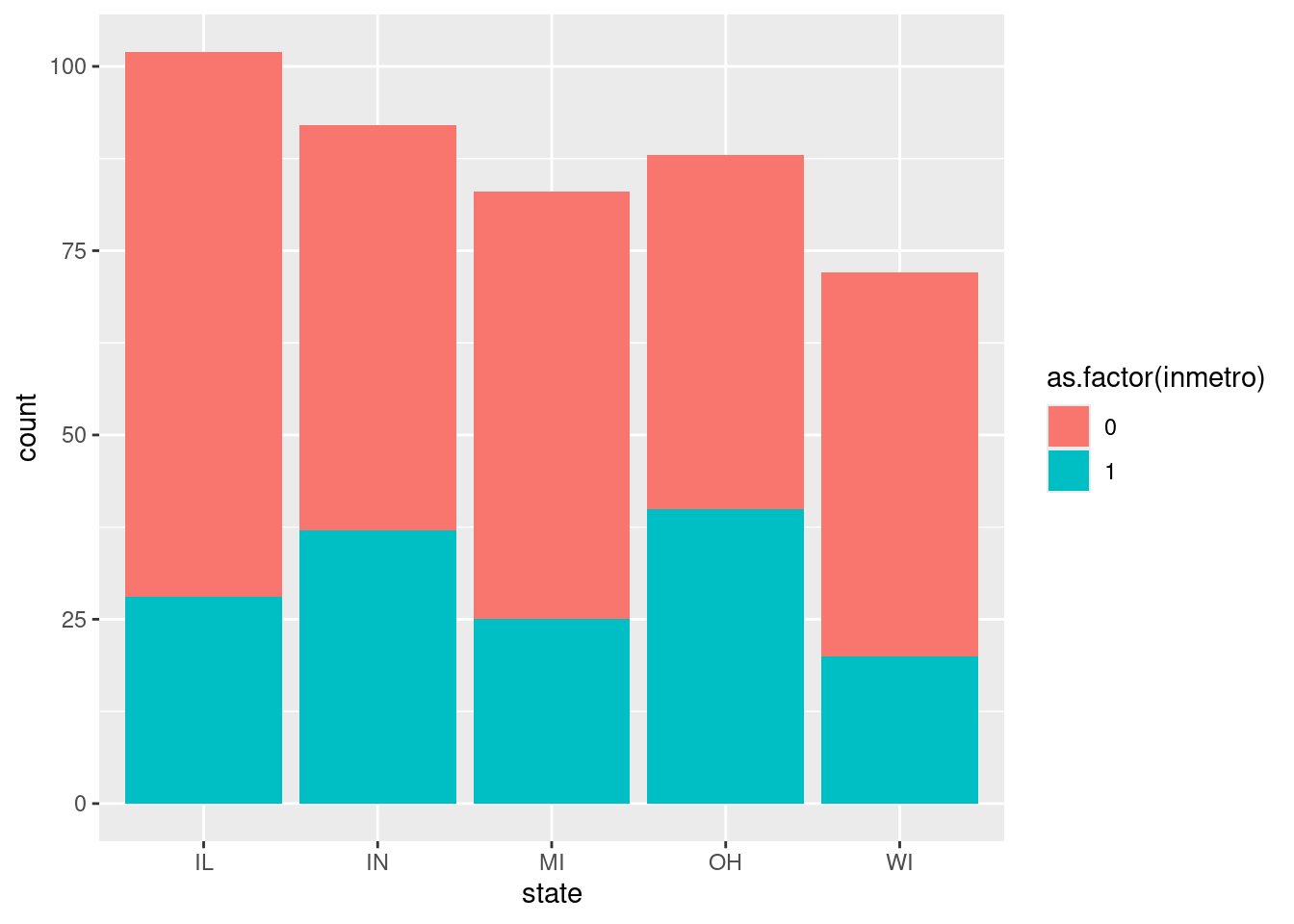

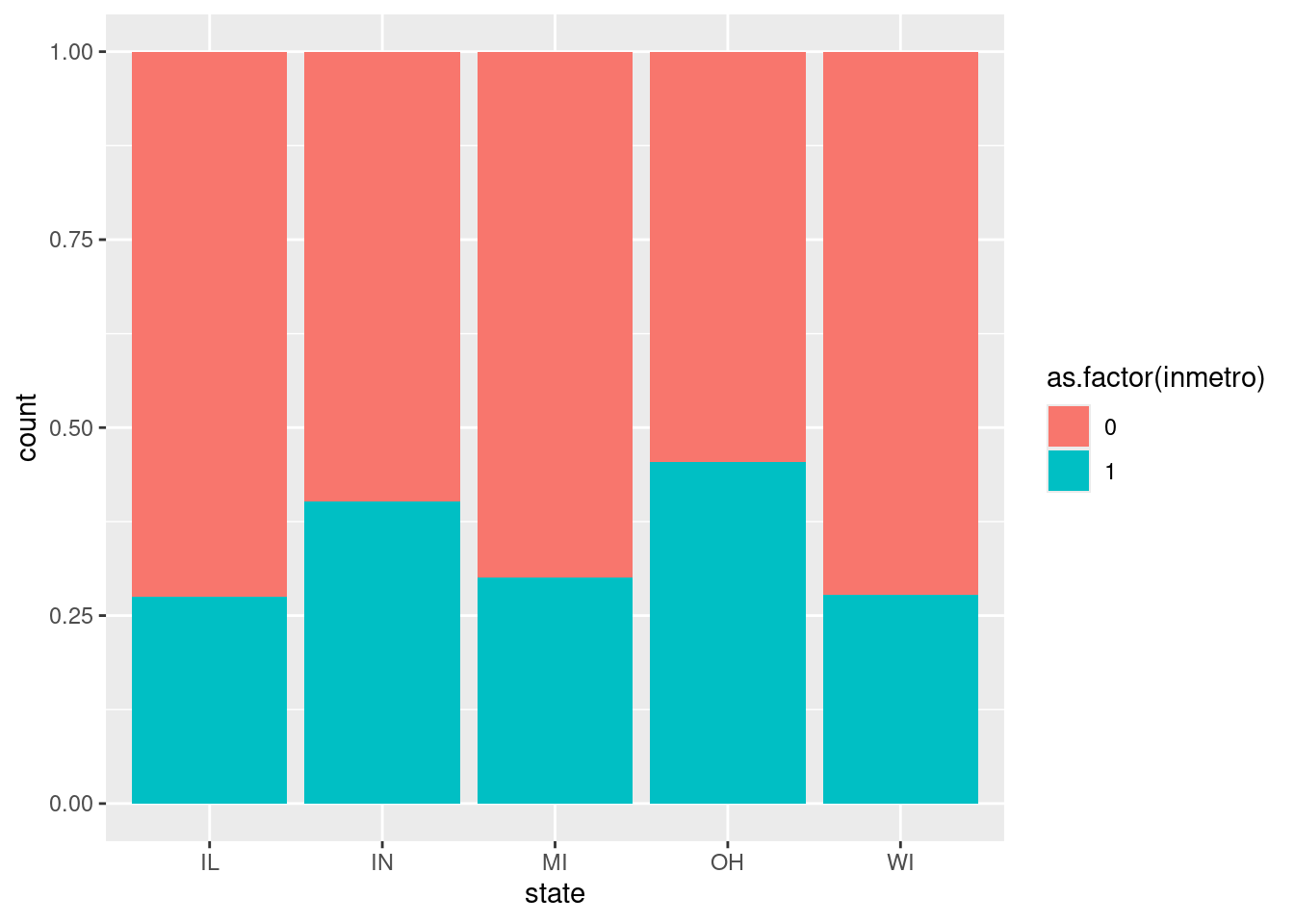

$ state <chr> "IL", "IL", "IL", "IL", "IL", "IL", "IL", "IL", "…

$ area <dbl> 0.052, 0.014, 0.022, 0.017, 0.018, 0.050, 0.017, …

$ poptotal <int> 66090, 10626, 14991, 30806, 5836, 35688, 5322, 16…

$ popdensity <dbl> 1270.9615, 759.0000, 681.4091, 1812.1176, 324.222…

$ popwhite <int> 63917, 7054, 14477, 29344, 5264, 35157, 5298, 165…

$ popblack <int> 1702, 3496, 429, 127, 547, 50, 1, 111, 16, 16559,…

$ popamerindian <int> 98, 19, 35, 46, 14, 65, 8, 30, 8, 331, 51, 26, 17…

$ popasian <int> 249, 48, 16, 150, 5, 195, 15, 61, 23, 8033, 89, 3…

$ popother <int> 124, 9, 34, 1139, 6, 221, 0, 84, 6, 1596, 20, 7, …

$ percwhite <dbl> 96.71206, 66.38434, 96.57128, 95.25417, 90.19877,…

$ percblack <dbl> 2.57527614, 32.90043290, 2.86171703, 0.41225735, …

$ percamerindan <dbl> 0.14828264, 0.17880670, 0.23347342, 0.14932156, 0…

$ percasian <dbl> 0.37675897, 0.45172219, 0.10673071, 0.48691813, 0…

$ percother <dbl> 0.18762294, 0.08469791, 0.22680275, 3.69733169, 0…

$ popadults <int> 43298, 6724, 9669, 19272, 3979, 23444, 3583, 1132…

$ perchsd <dbl> 75.10740, 59.72635, 69.33499, 75.47219, 68.86152,…

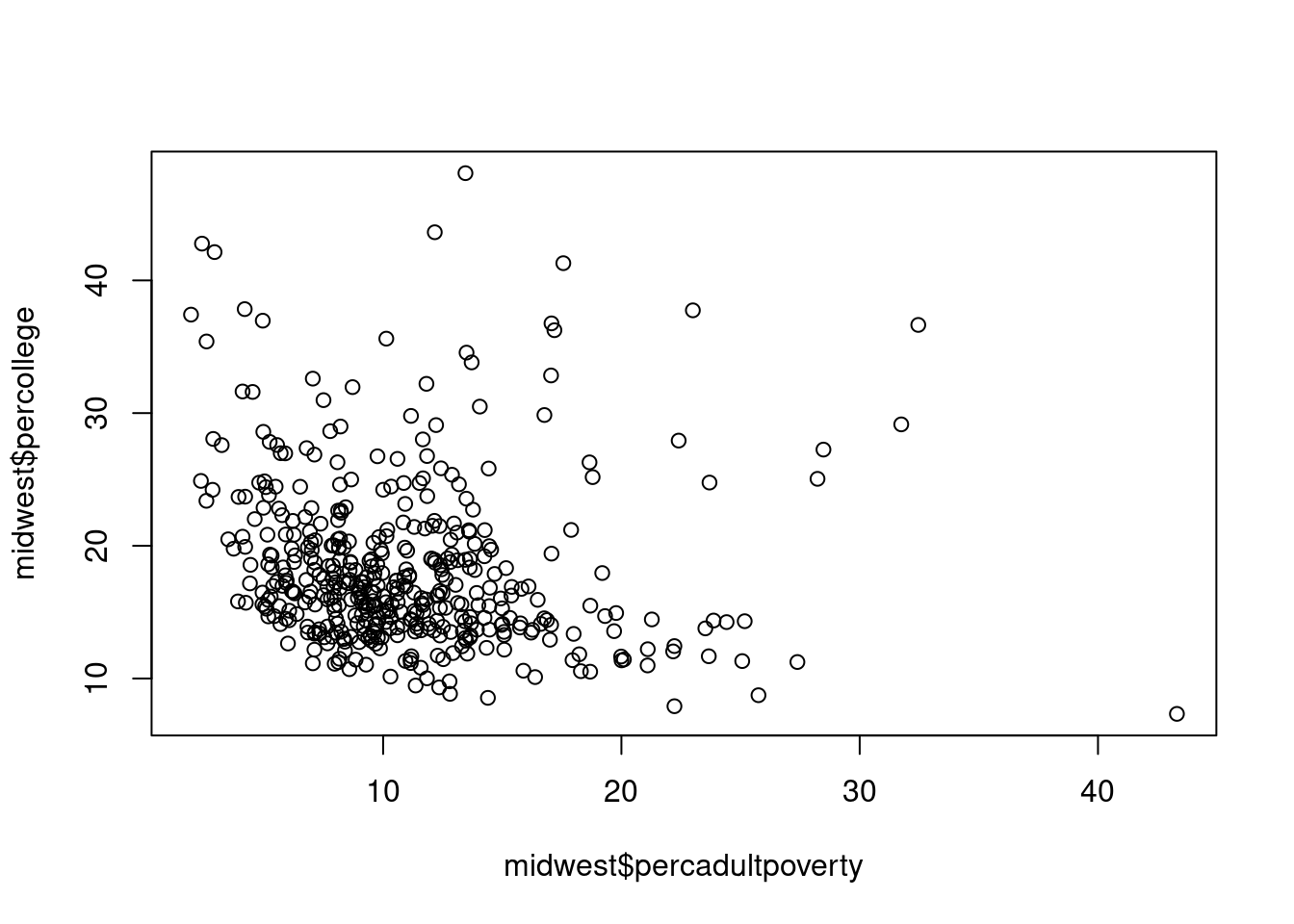

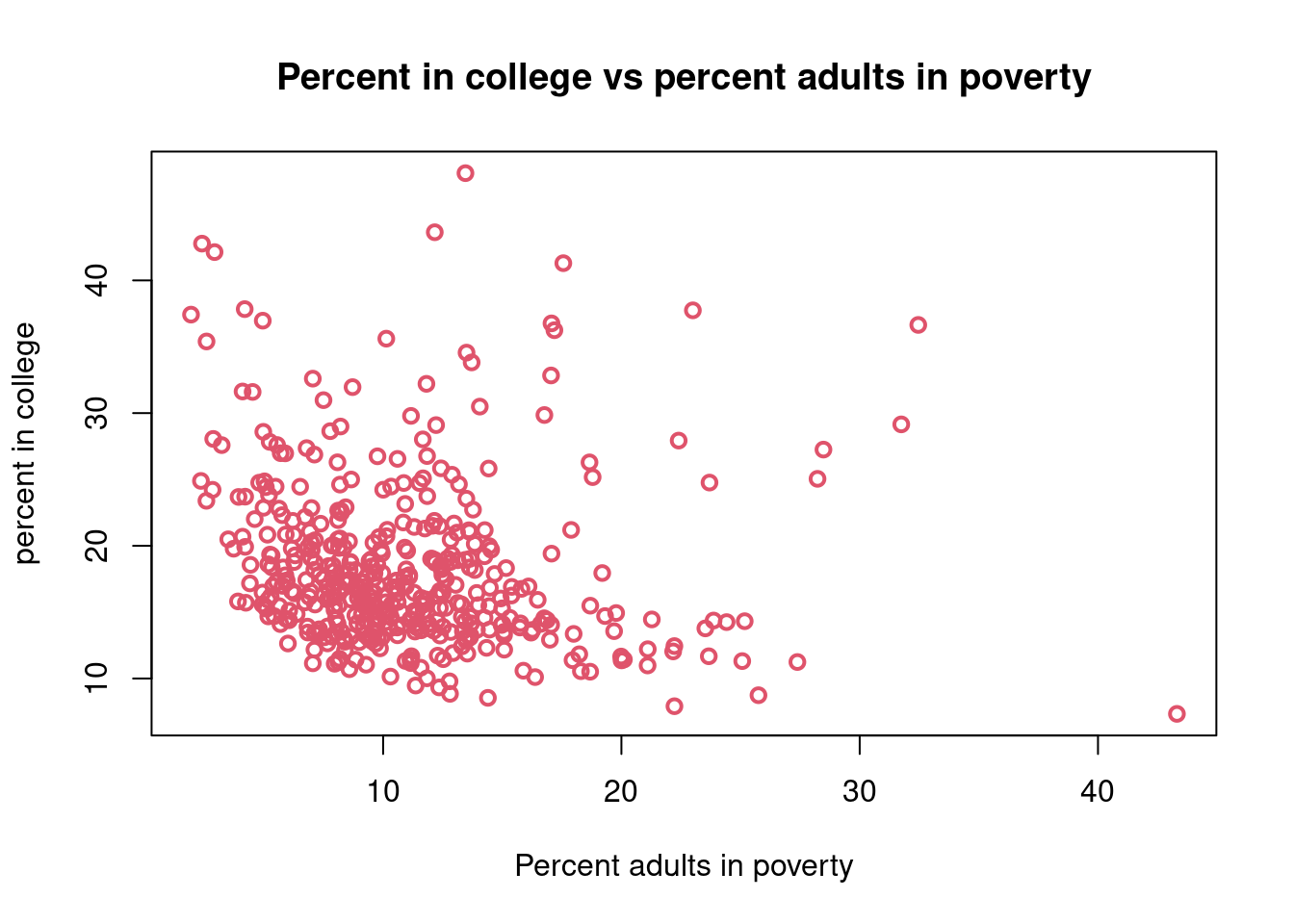

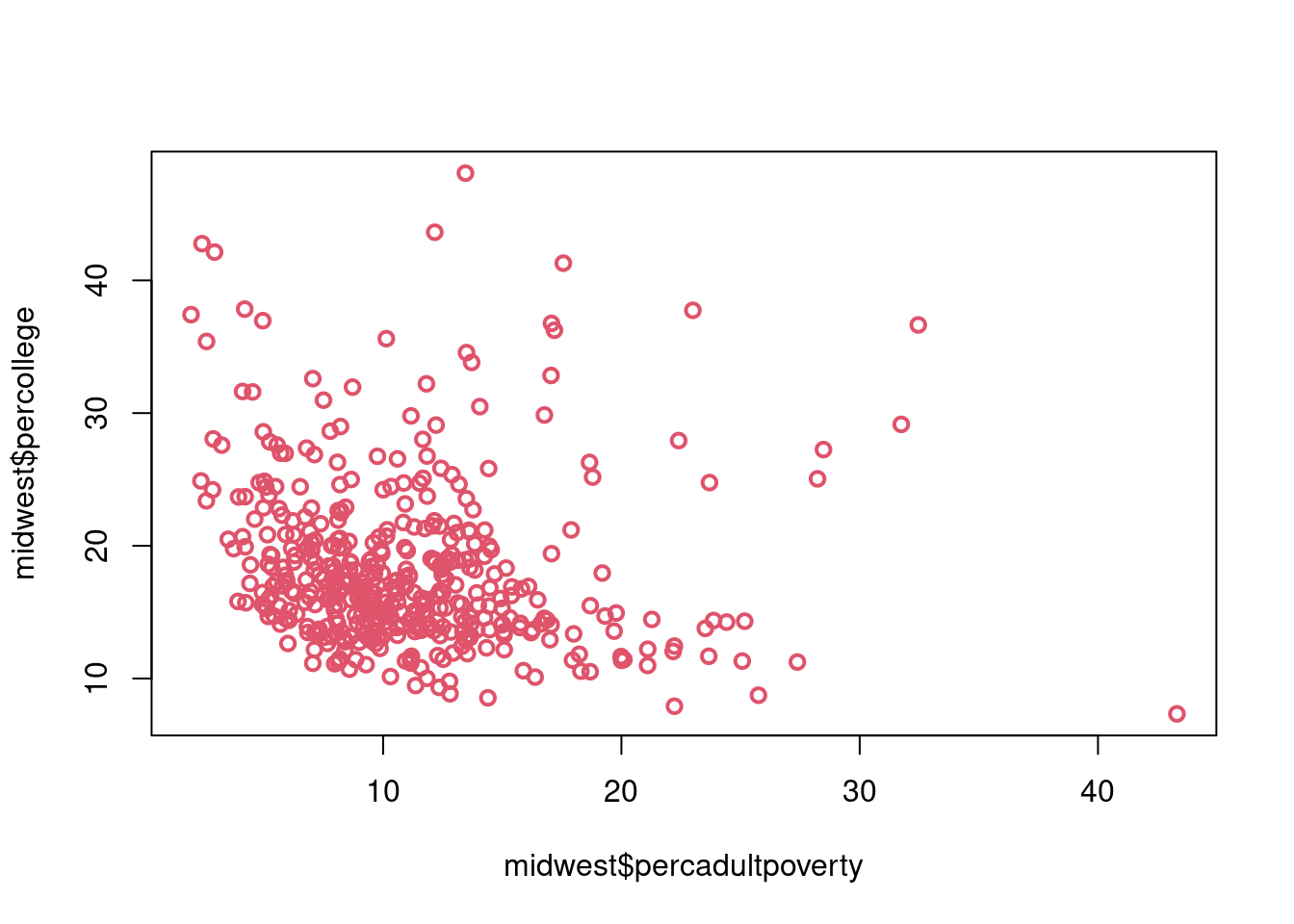

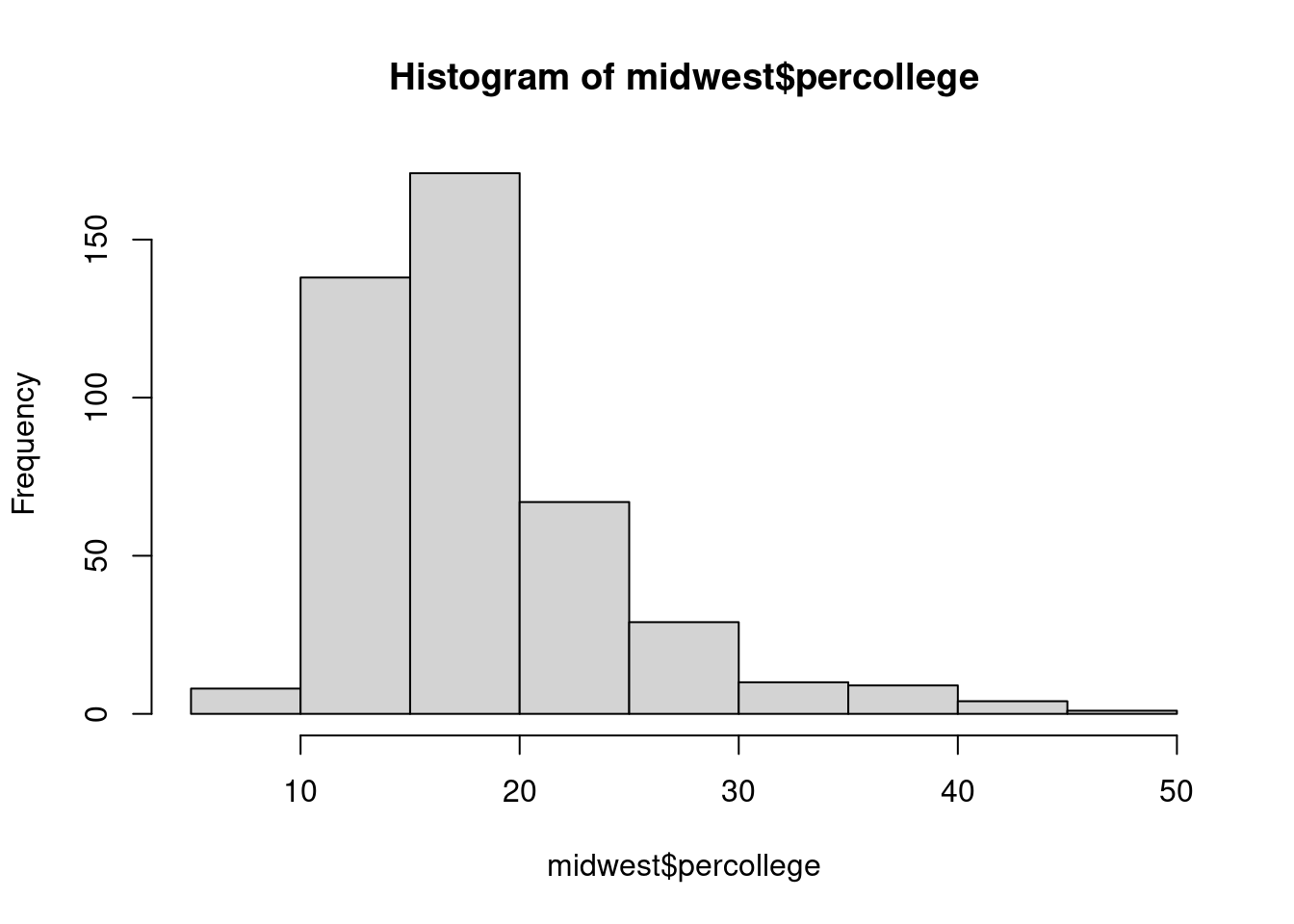

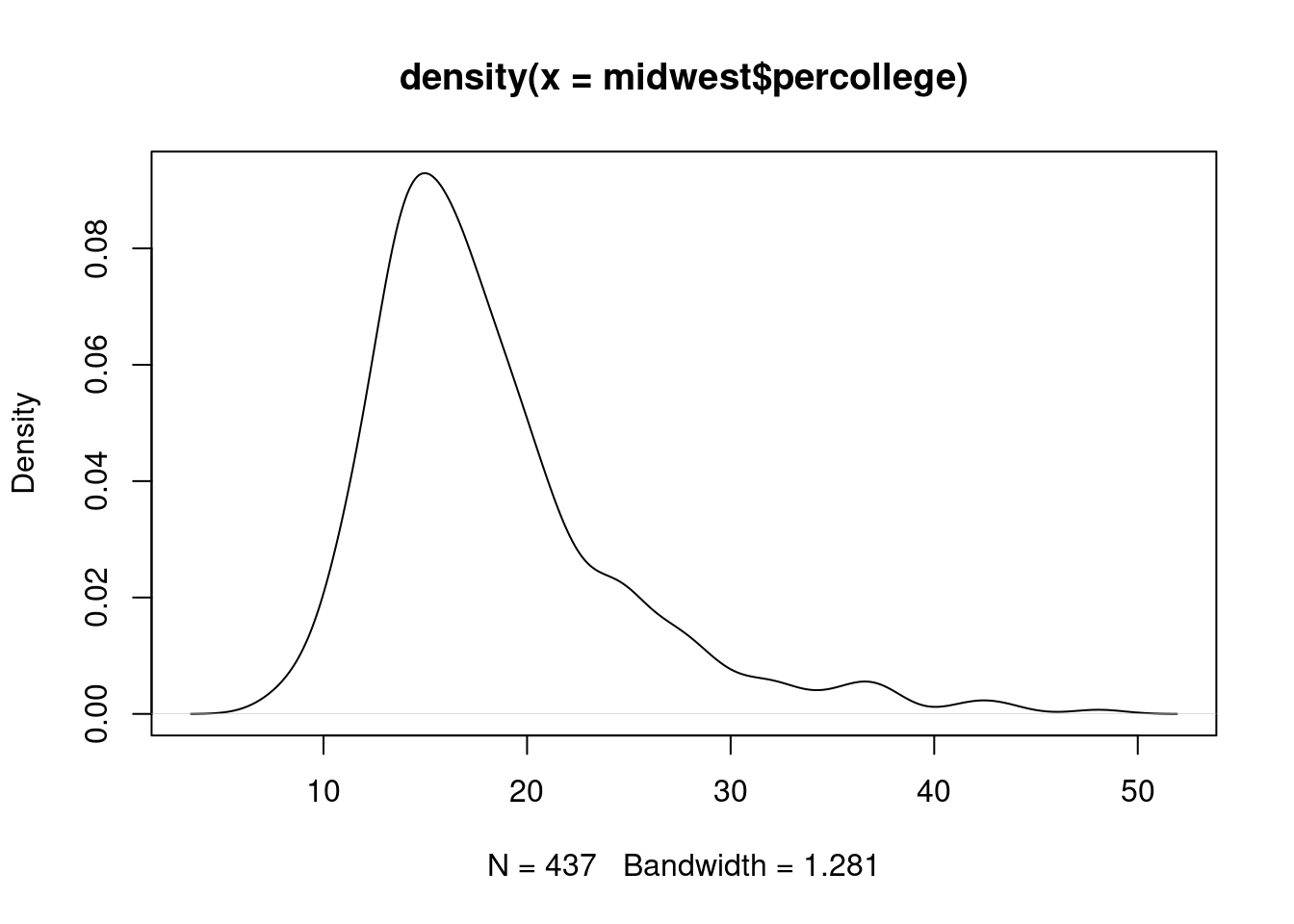

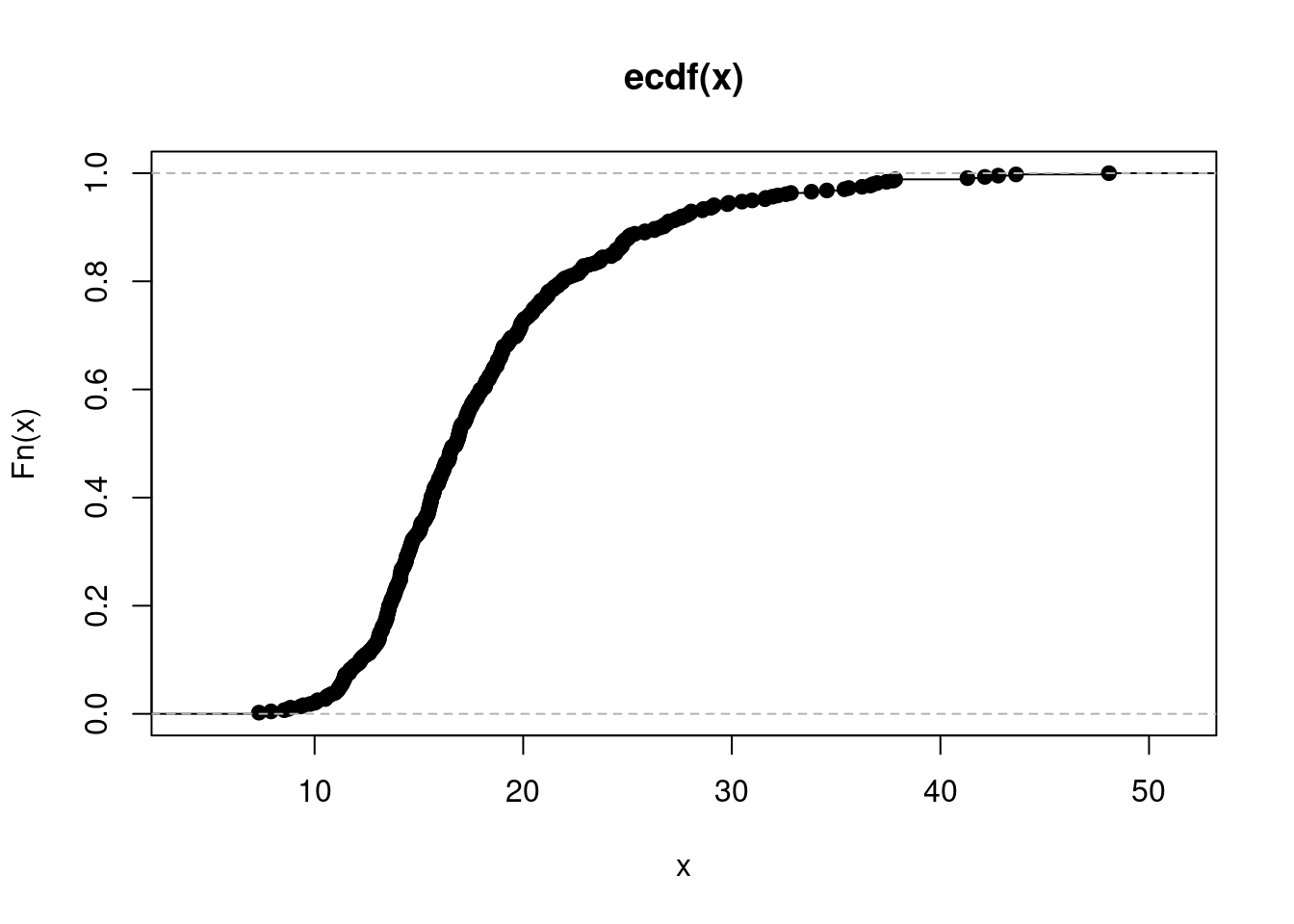

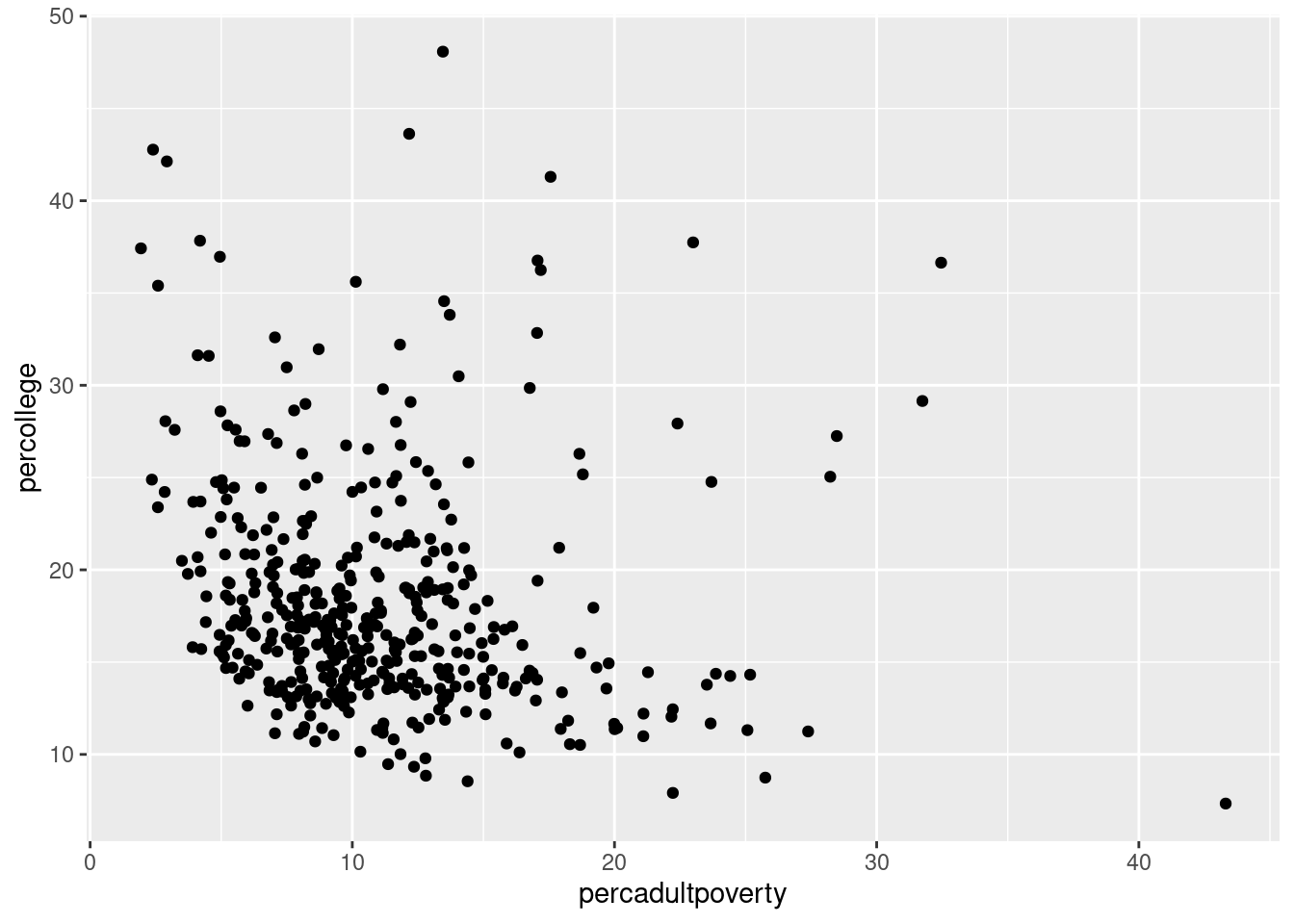

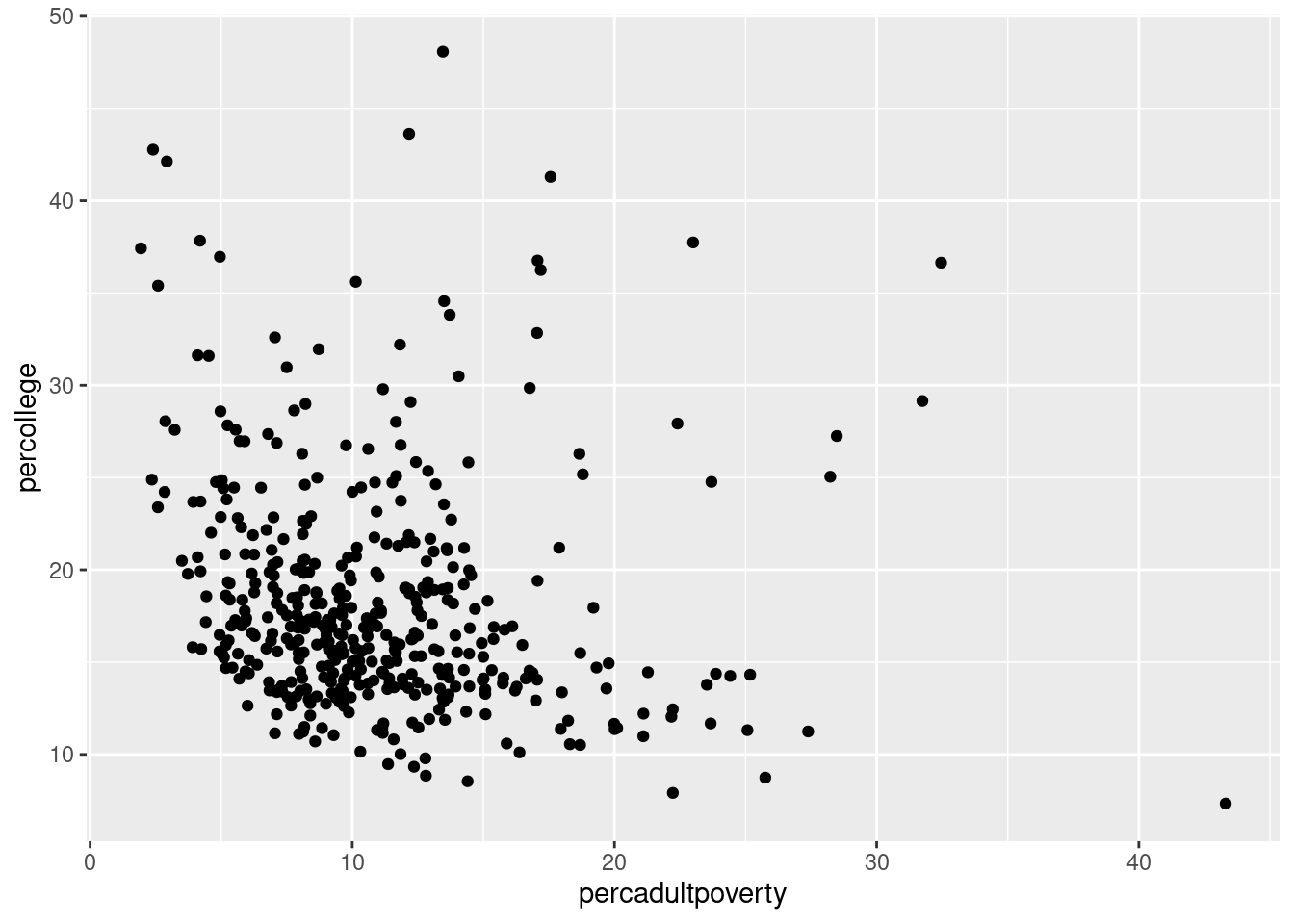

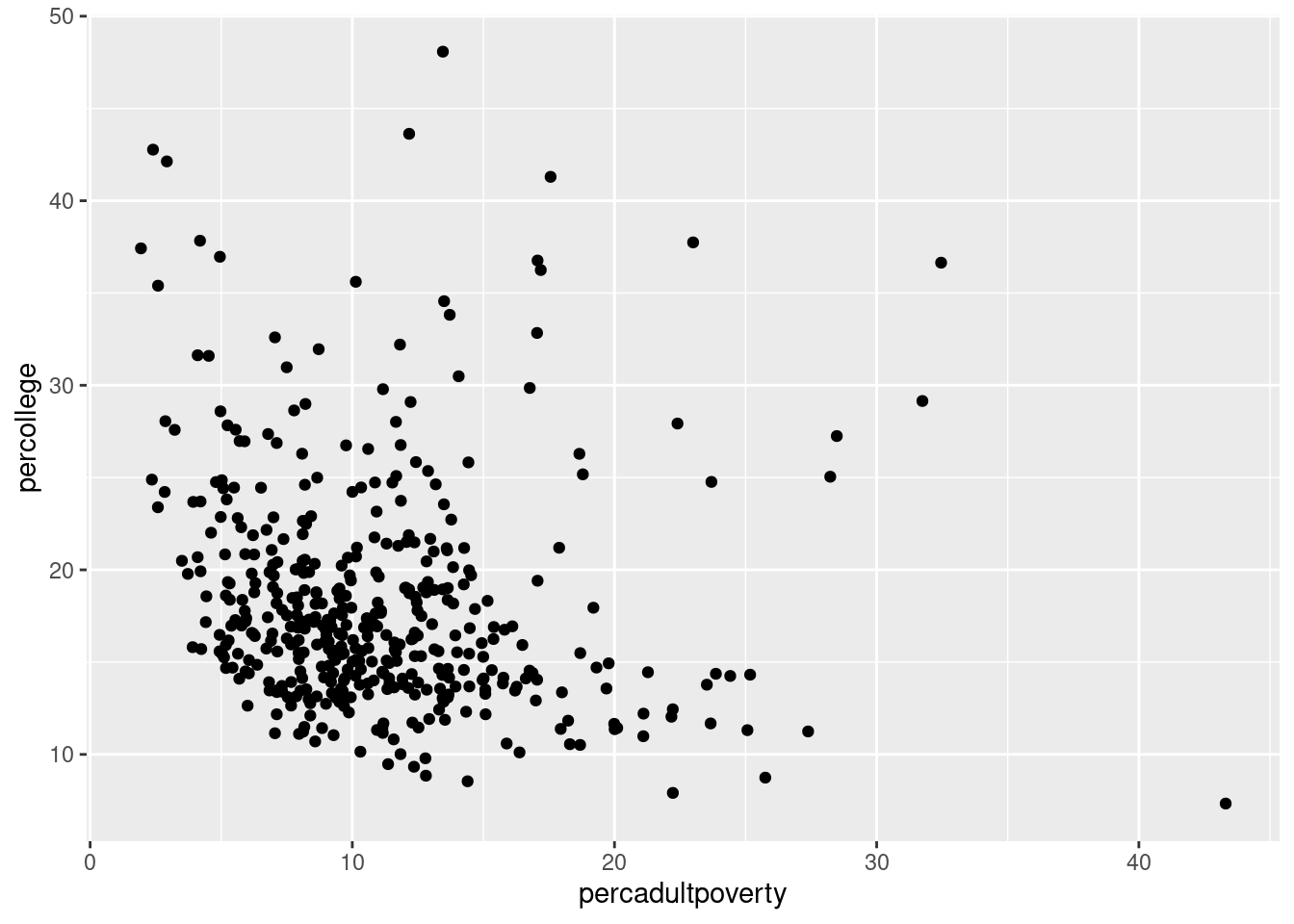

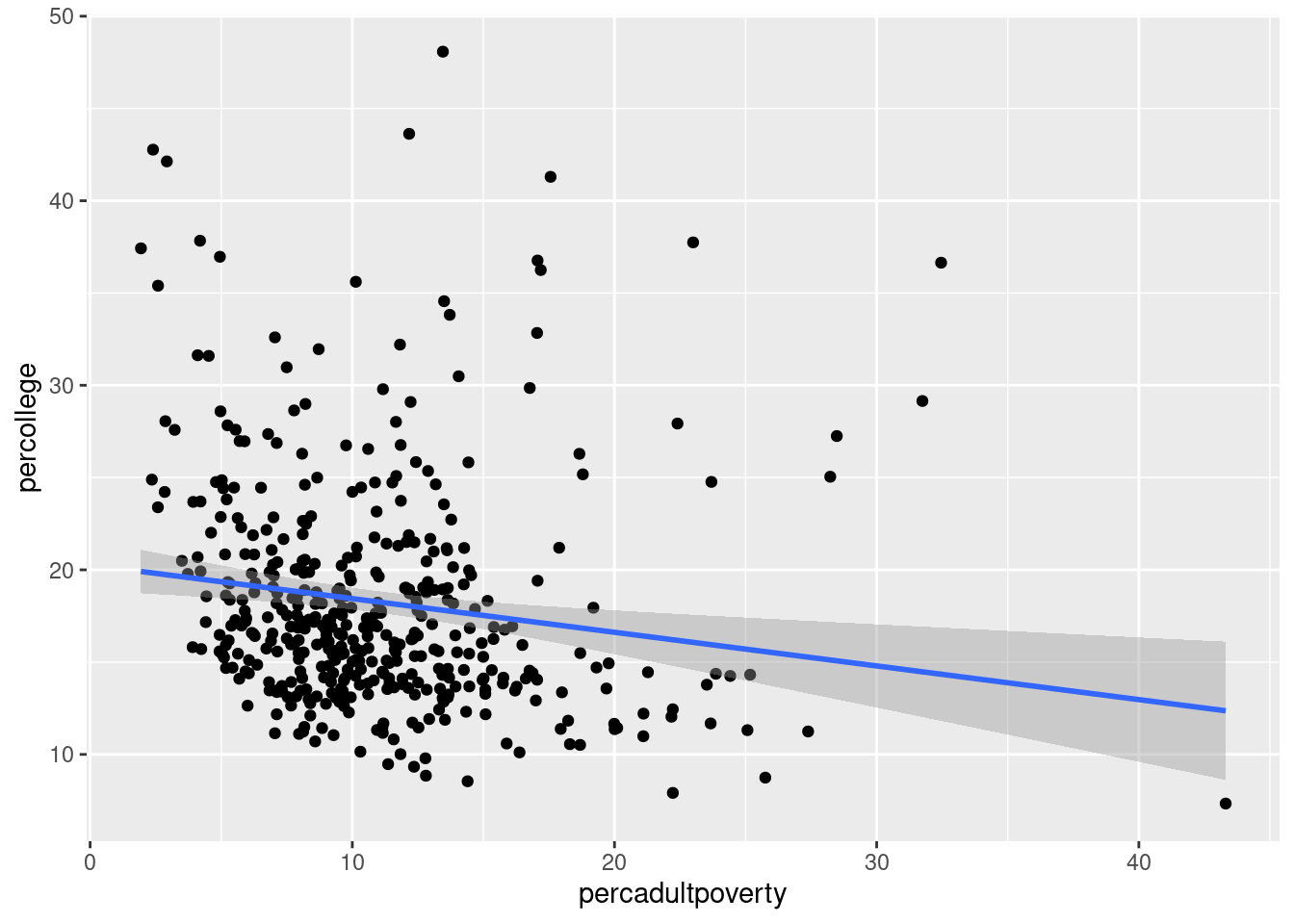

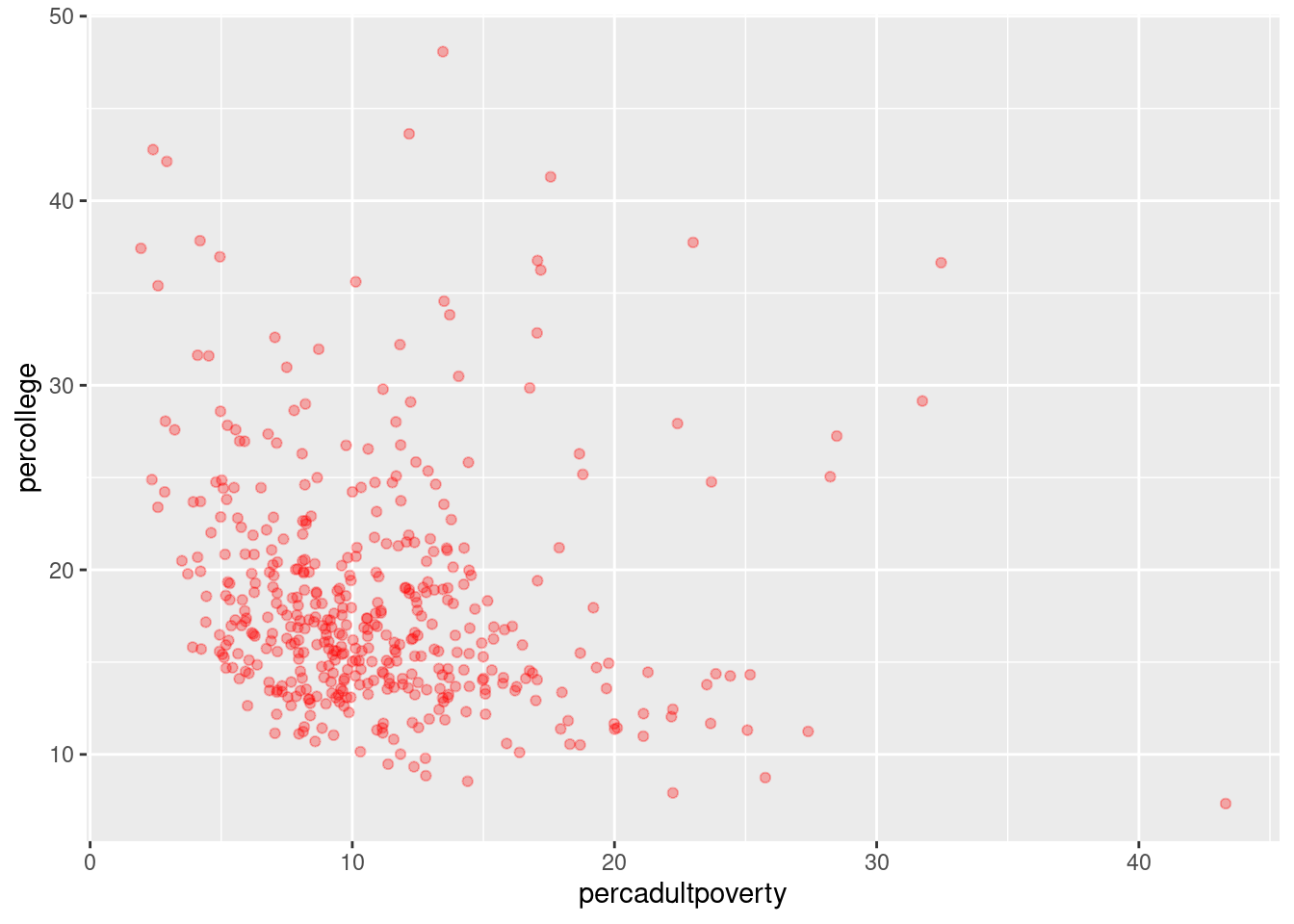

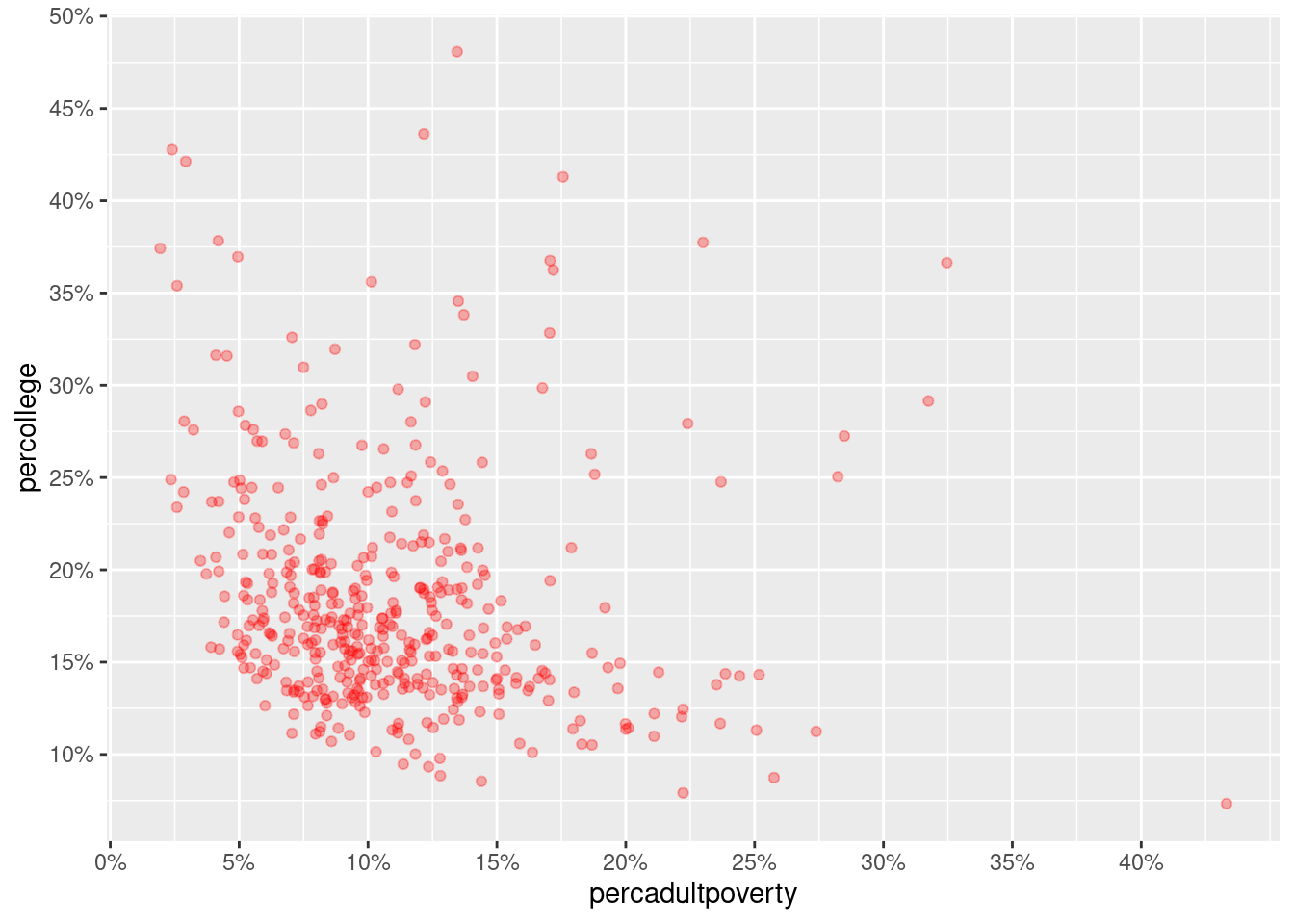

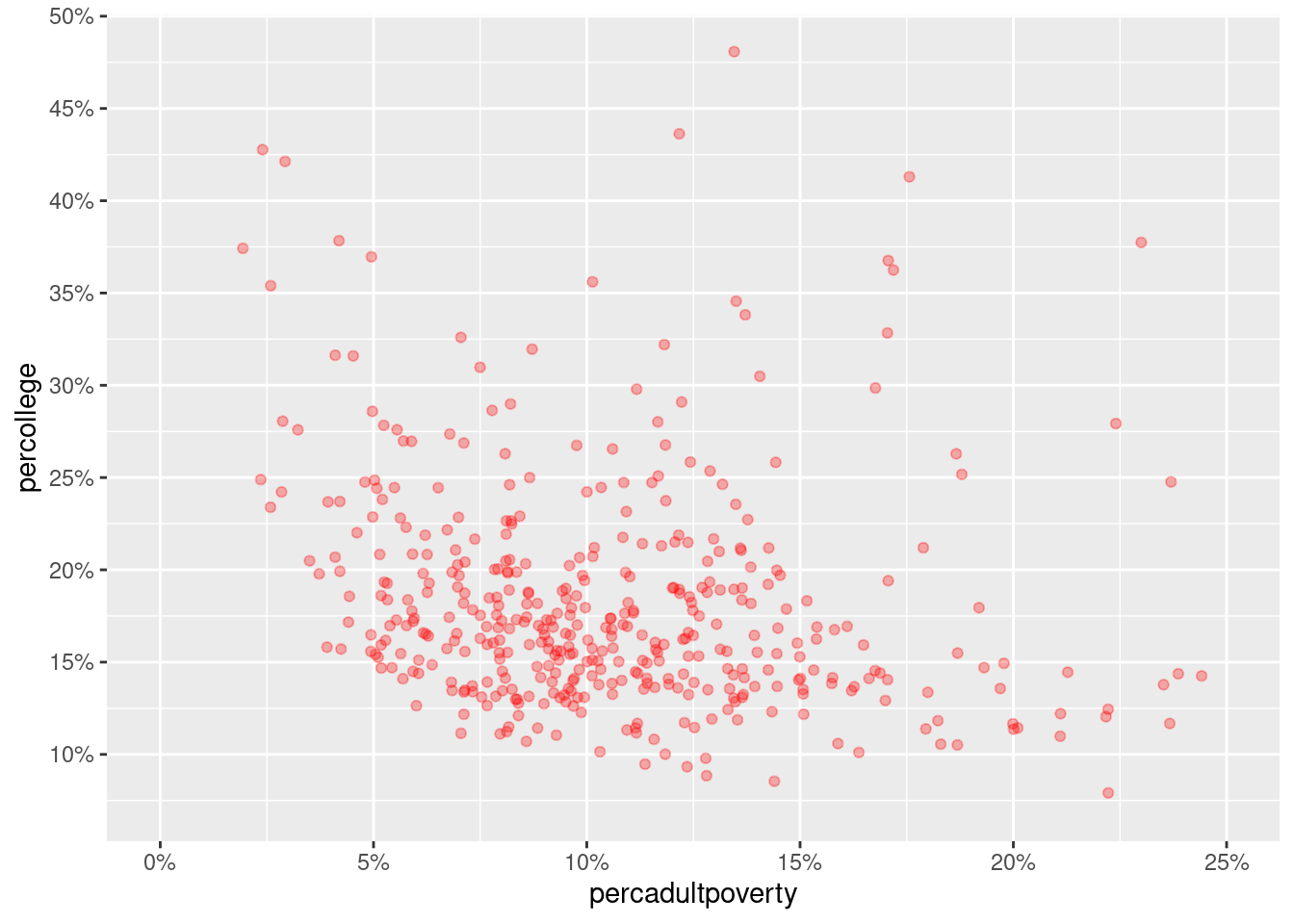

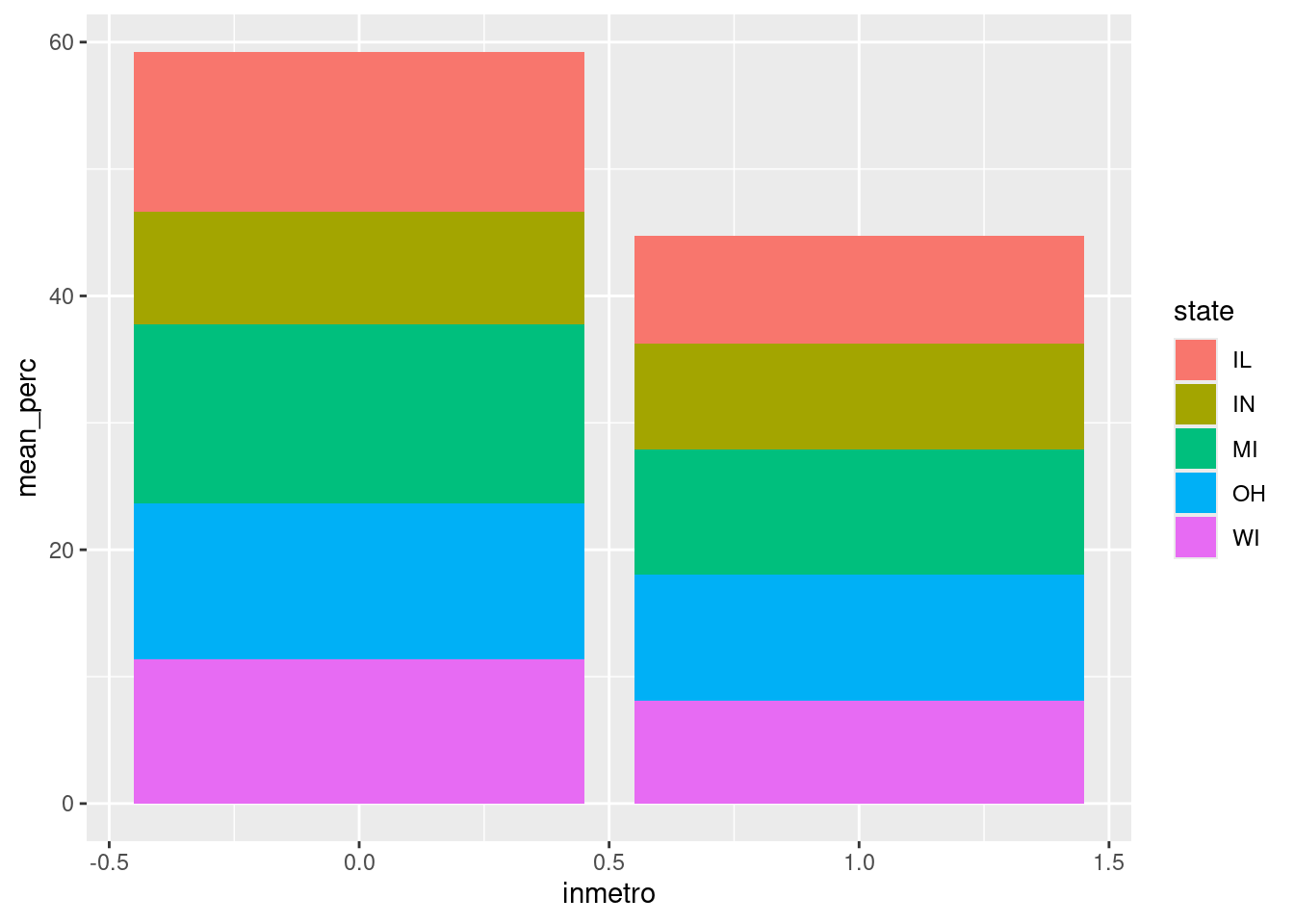

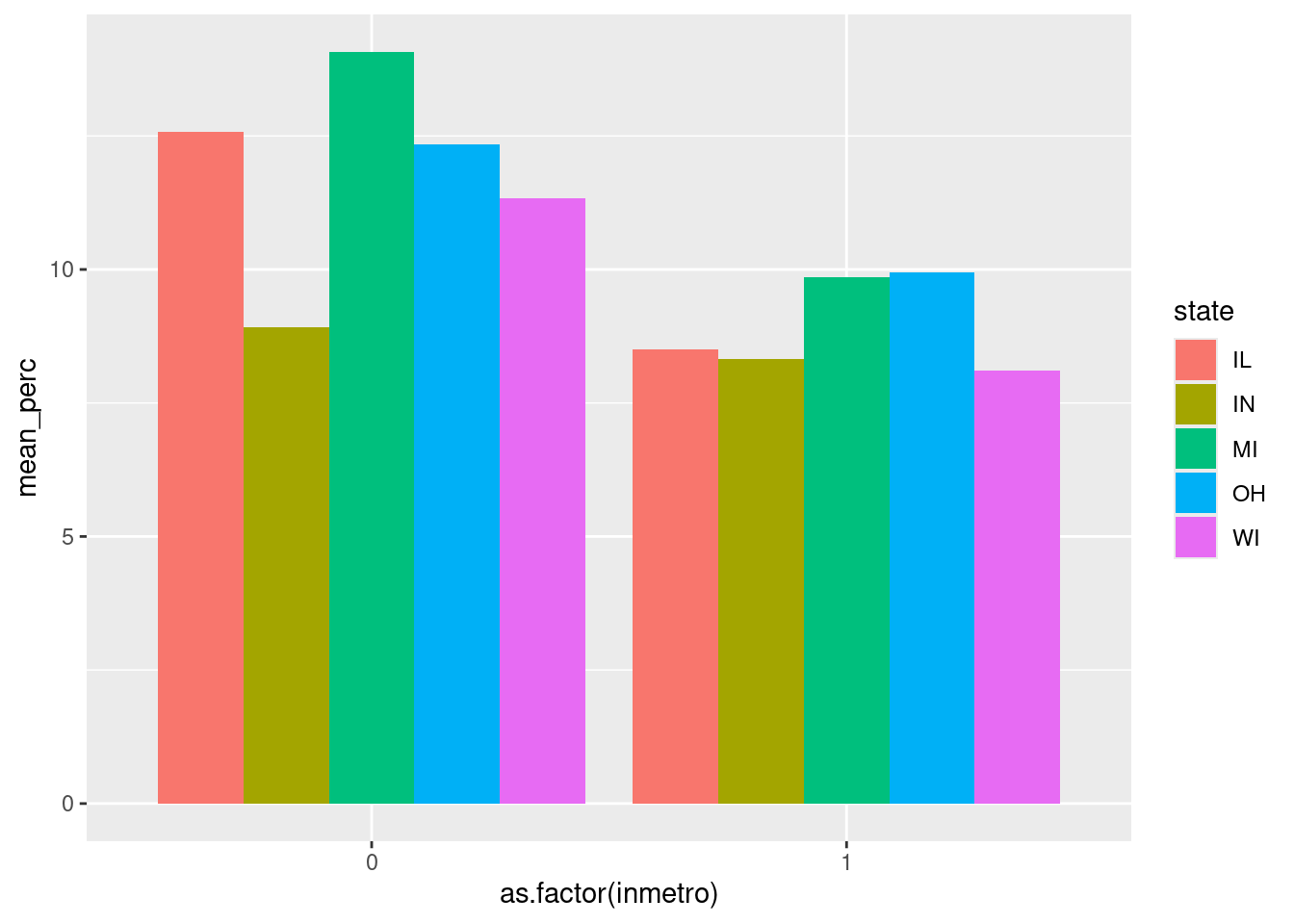

$ percollege <dbl> 19.63139, 11.24331, 17.03382, 17.27895, 14.47600,…

$ percprof <dbl> 4.355859, 2.870315, 4.488572, 4.197800, 3.367680,…

$ poppovertyknown <int> 63628, 10529, 14235, 30337, 4815, 35107, 5241, 16…

$ percpovertyknown <dbl> 96.27478, 99.08714, 94.95697, 98.47757, 82.50514,…

$ percbelowpoverty <dbl> 13.151443, 32.244278, 12.068844, 7.209019, 13.520…

$ percchildbelowpovert <dbl> 18.011717, 45.826514, 14.036061, 11.179536, 13.02…

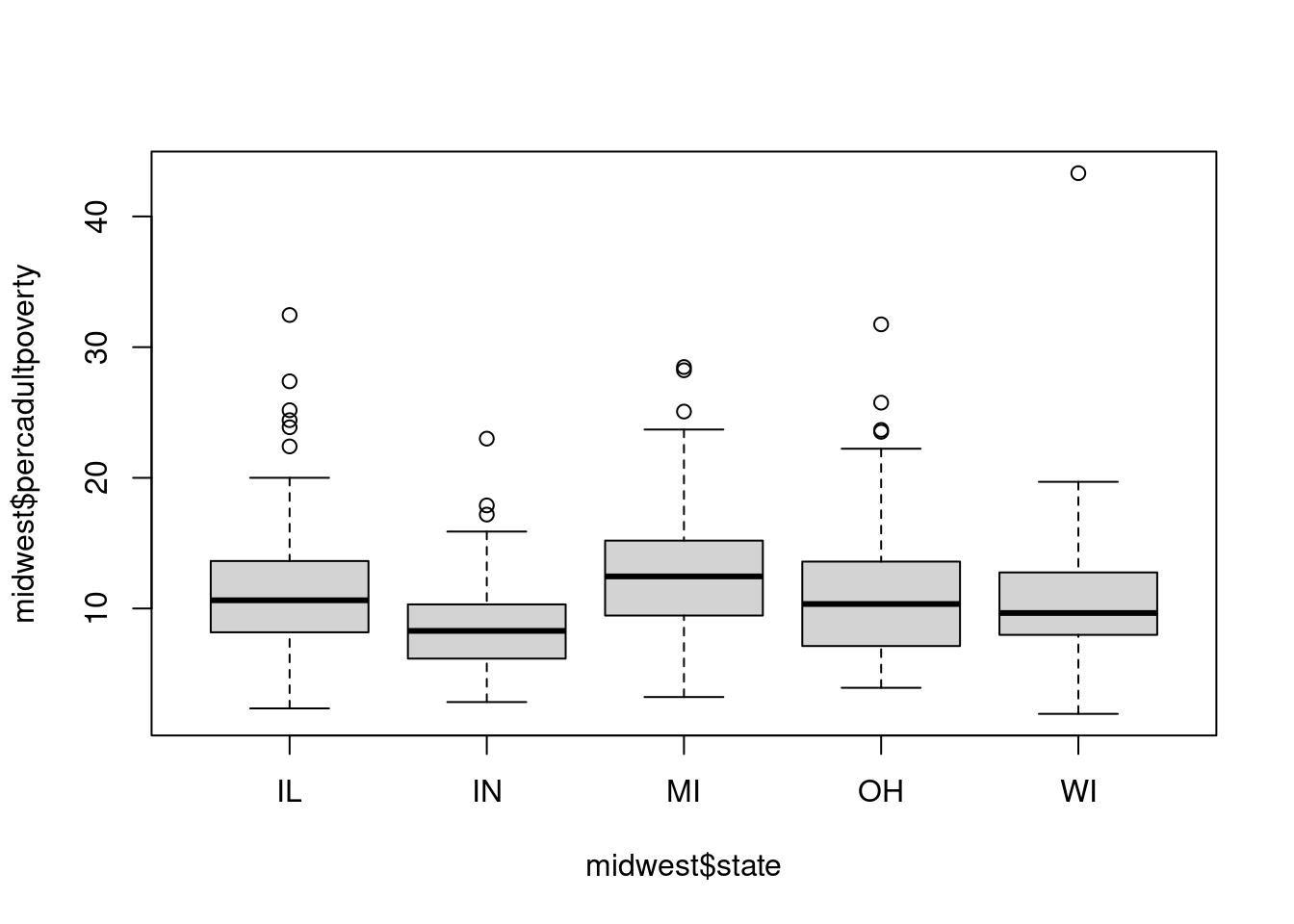

$ percadultpoverty <dbl> 11.009776, 27.385647, 10.852090, 5.536013, 11.143…

$ percelderlypoverty <dbl> 12.443812, 25.228976, 12.697410, 6.217047, 19.200…

$ inmetro <int> 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0…

$ category <chr> "AAR", "LHR", "AAR", "ALU", "AAR", "AAR", "LAR", …